"Eastern Right": Rod Dreher on Orthodoxy and Political Conservatism

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Tuesday, June 26, 2012 at 12:24AM

Tuesday, June 26, 2012 at 12:24AM When I opened the June issue of The American Conservative (TAC) last night, I was greeted by this article from Rod Dreher. The following comment from the article stood out to me in light of the combox discussion that recently took place here at OJC ("For Evangelicals and Others Considering Eastern Orthodoxy", hereinafter "Considering Orthodoxy"):

On a practical level, any conservative who believes he can escape the challenges of modern America by hiding in an Orthodox parish is deluded. All three major branches of Orthodoxy in America have suffered major leadership scandals in recent years. And while Orthodox theology does not face the radical revisionism that has swept over Western churches in the past decades, there are nevertheless personalities and forces within American Orthodoxy pushing for liberalization on the homosexual question. And in some parishes—including St. Nicholas OCA Cathedral in Washington, D.C.—they are winning victories.

Dreher therefore corroborates what both Fr. Gregory Jensen and I have experienced in the Orthodox Church, as I set forth in "Considering Orthodoxy", which is the increasing "Episcopalianization" of that communion. If that weren't enough, several individuals commenting at Dreher's TAC article have also experienced it, and at least one person commenting there is an Orthodox Episcopalianizer. The two individuals commenting at my "Considering Orthodoxy" article, Fr. John Morris and an "Orthodox Christian" who represents himself as a recently minted deacon, protested loudly about the liberalism charge, but here is yet one more witness to its reality in the Orthodox Church. I reiterate, therefore, my caveat emptor to Evangelicals (who tend to be politically and culturally conservative) and other traditionalists considering Orthodoxy.

Here are some quotable quotes from the combox discussion at TAC (where, by the way, Fr. Morris carries forth his desperate apology):

As to Americans going to Russian or other Orthodox churches, I would have thought that men deserving of the name would stay and fight for what is theirs. Not slink off to someone else’s church, except under the sort of conditions that led to so many Protestants coming to this country in the first place. Until such conditions obtain here the rubric should be “I’ll take my stand” rather than “I’ll stand over there instead”.

______________________________________________

Interesting piece, although, I think the bishops census of only 800,000 Eastern Orthodox adherents in the USA seems off by several million… And, more importantly, aside from the admittedly compelling, ancient beauty of its churches and liturgies, there can only be a tiny minority of Orthodox adherents or converts who experience or understand the church and its teachings at the level discussed in this piece. One wonders where the author and some of those commenting here are plugging into Orthodoxy. It cannot be solely from their experiences attending services or bible classess, can it?

Having grown up in a large Catholic enclave, and judging from what we constantly see going on in the headlines, on contraception, gays and gay marriage, abortion, sexuality in general, etc., I’ve always experienced the Orthodox church to be relatively liberal and non-doctrinaire, particularly when compared to Catholicism and many other US Christian denominations. I know Orthodoxy has largely conservative, unchanging views on all of these “values” issues, which do not substantively differ from those flowing from Catholic or Evangelical doctrine, but Orthodoxy does not seem to spend much energy on any of it, at least not here in the US. It has always felt more like “don’t ask, don’t tell”, its all good, do the best you can with your personal circumstances, God is with you just the same.

And, we’ll never see any Orthodox clergyman in the US refusing an Orthodox politician Communion because the politician commits to enforcing the laws of the land even if they may conflict with his personal views or the teachings of his church. We’re also not very likely to see any Orthodox clergyman suing the government…

________________________________________________

Four years ago I resigned as the Rector of an Episcopal Church, left a decade long priesthood, renounced my orders, and along with the rest of my family became Eastern Orthodox. The particular jurisdiction that we became a part of was the Orthodox Church in America. I was sent by my Archbishop to an Orthodox Seminary in Pennsylvania for a year.

My family gave up a great deal so that we could become Orthodox, and we didn’t expect to be congratulated for that, but didn’t expect the cold reception that we got from many quarters either. We were ready to embrace Orthodoxy wholeheartedly, but never really felt like we were embraced back. The Sacraments that I had administered during my ten years of priestly ministry in the Episcopal Church were repeatedly characterized as being without any validity for the people I served. But, despite the arrogance, we found the OCA to be every bit as dysfunctional an institution, in it’s own way, as is the Episcopal Church. There seemed to be a disconnect between the sublime theology of the Church Fathers and our actual experience in the OCA. The reality we found in the OCA as an institution included an ethnocentric insularity and xenophobia among a great many ethnic Russians; anti-Semitism; a latent fundamentalism among a great many of the converts; shocking corruption and abuse of power in the hierarchy; and a good deal of hateful anti-Americanism among immigrant priests and monks, and even some American ones, that caused some members of my family to struggle with their faith in ways that they never had to do while we remained Anglican. That is perhaps the most pertinent reason that we decided to return to the Anglican Communion. But still it was a gut wrenching decision to make.

I was drawn to the Orthodox Faith because of it’s faithfulness to the ancient understandings of the Faith. My theology is very heavily informed by the theology of the Orthodox Church. I understand sin as bondage and sickness rather than as transgression. As a result, I have an Orthodox transformative understanding of salvation rather than a judicial one, meaning that the real object of salvation is God effecting an inner change in us. Again, the model of atonement I have is an Orthodox one of recapitulation, rather than appeasement. In other words, the need for the atonement was not to satisfy a need God had for punishment, but rather to recreate in us the image of God that we had lost, and to free us from the bondage of sin. I also share with the Orthodox church the focus on theosis – our participation in the divine life which changes us into the likeness of Christ. In that sense I see salvation not as a one time act, but as a growing relationship with God. I also am certain that the Orthodox church is right in their understanding of original sin, not as inherited guilt, but as our inheriting the consequences of living in a sinful world.

There is nothing keeping me from believing as I do and being Anglican. The Orthodox Church is however, at least as I have encountered it in the OCA, very defensive and aggressively anti-Western whenever talking about differences that exist between the two, no matter how small, no matter how long ago. I’m sorry but I’m simply not interested in nursing some old grudge about the Fourth Crusade, or about Eastern-Rite Roman Catholicism in the Ukraine. The Eastern Orthodox can be very enthusiastic grudge-holders.

I found that I needed to return to the Anglican Communion because I am culturally a Western Christian, and I see more clearly now than I did two years ago that the Western culture I was raised in is an inseparable part of who I am. It cannot be set aside without setting aside some things basic to who I am. Some might say, “What profit is there in saving your culture only to lose your soul?” However, I think that would be a false dichotomy. As I look around at the mostly eastern European congregations that are gathered in any Orthodox Church during the Divine Liturgy, I see that it is most often said at least partly in Slavonic, Greek or some other eastern language. It is obvious to me that, for those congregations, their ethnic identity and their being Christian are practically co-terminus. And perhaps that is not entirely a bad thing. The Christian Faith is fundamentally incarnational, and thus it naturally incarnates itself in a culture — be it Russian, or Greek, — or American, or British, or Chinese, or whatever.

I do not now belong to the Eastern Orthodox Church because I am not culturally Eastern, and I am unwilling and unable to live my life as a pretend Russian, or a pretend Greek. The faults of the Western Churches are the faults of Western culture. Eastern Orthodox Churches suffer from the faults of Eastern cultures. In the words of John Henry Newman, ”the Nation drags down its Church to its own level.”

Simply put, I was born and raised in the West so I am a Western Christian, I don’t think that I have any real option to be anything other than that. I have returned to trying to live out the ancient faith as best I can in the place in which I was raised and live. The Eastern Orthodox world, despite the things that it has to commend it, nevertheless has it’s own profound problems and I don’t think that running to it is the answer to what is wrong in the Western Church.

That last comment was, of course, particularly apropros. Though I don't agree with every sentiment expressed therein, he got to the nub of it in his comments about Orthodox anti-Westernism. If you convert to Eastern Orthodoxy, prepare to check your execrable Westernism at the door and to embrace the Eastern Orthodox ( = Byzantine) "phronema."

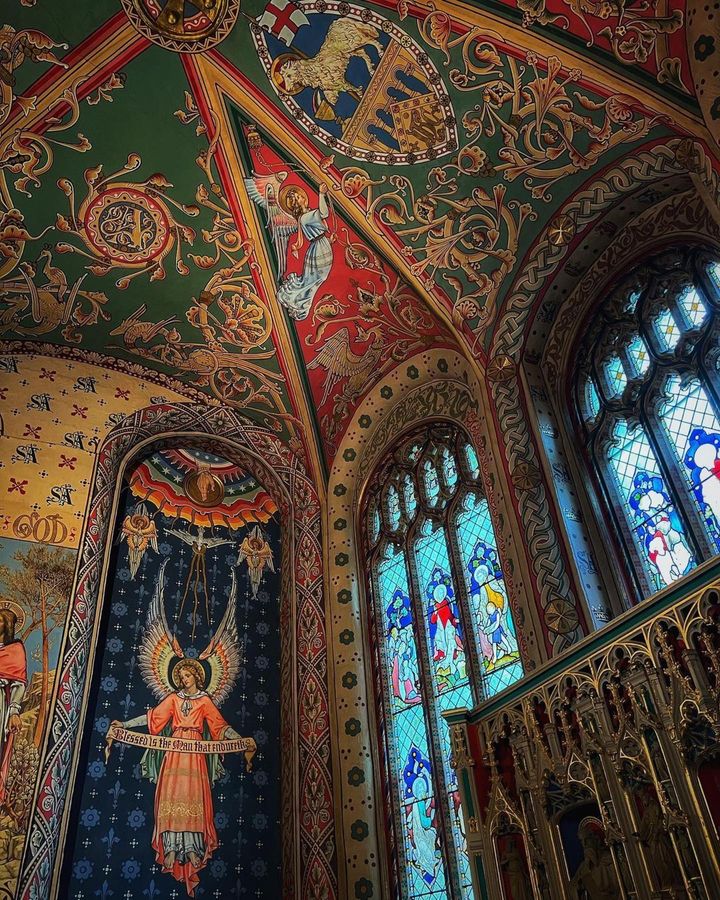

A Bit of Anglican Sacred Space at the Foot of the Ozarks

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Sunday, June 17, 2012 at 06:34PM

Sunday, June 17, 2012 at 06:34PM St. Matthew's Anglican Church (UECNA), Rogers, AR, where I attended Mass this morning. (My wife and I are here in NW AR visiting relatives.) A wonderful bunch of people led by a wonderful priest, Fr. Jerry Ellington. May God continue to bless Continuing Anglicanism in Northwest Arkansas through this parish.

How To Become A Christian

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Tuesday, June 12, 2012 at 01:06PM

Tuesday, June 12, 2012 at 01:06PM A statement from a former metropolitan of the Anglican Catholic Church, M. Dean Stephens:

Just What is Faith in Christ, Anyway?

A message from the Most Rev. M. Dean Stephens, Metropolitan of the Anglican Catholic Church and Archbishop Ordinary of the Diocese of New Orleans, reprinted from The Trinitarian,

Volume XV, No. 1, February, 1996.

If I were to ask you, "Do you have faith in Christ," how would you answer? Some of you would answer in the affirmative with a resounding "yes". Others might answer, "I'm not sure that I have any faith." Still others would respond by saying, "Is it possible to know if one has faith in Christ? What is faith anyway?"

The question about faith in Christ is of the utmost importance because the Bible says that, "Nor is there salvation in any other; for there is no other name under heaven given among men whereby we must be saved" [Acts 4:12]. God has appointed one man, the man Christ Jesus in whom we must be saved. There is no other name or revelation that God has given mankind which will save us from the judgment to come or give life full meaning now. But what a glorious name, the name of our Lord Jesus!

Gabriel, the Angel of the Annunciation, told the Virgin Mary that the child to be conceived in her womb by the Holy Spirit was to be called Jesus, which means -- "God is Help," or more succinctly, "Captain of our Salvation." Jesus is the beginning and the end of our salvation. He is, in himself, the guarantee that we shall be saved if we believe in Him. Romans 10:9 tells us, "That if you will confess with your mouth the Lord Jesus and believe in your heart that God has raised him from the dead, you shall be saved."

But you say: "What does it mean ïto have faith,to believe? That’s a question that many have wrestled with. When, as a young teenager, I heard that I was to believe in Christ to be saved, I questioned in my own heart as to whether I had faith to believe in Christ as Saviour. Was my faith strong enough to save me? Was it real faith?

The word "believe" in today's language has changed and does not fully convey its full meaning of "trust" as it did a century or two ago. To "believe" actually means "to commit oneself to, to trust, cling to, or rely on." Today, in this latter part of the 20th century, you may "believe" something to be true, but not necessarily act upon that belief. Let me give you two simple examples.

We all know that if a person stands in the middle of a busy highway that he will be hit by oncoming traffic if he doesnÍt move. We all believe that to be a true statement of fact. However, the person may not act upon that belief and remove himself from harm. In that case, we all know what will happen. It is possible to believe something to be true but yet not act upon its truth.

A second example is of a person who is sick and will die if the right medicine isn't administered. If that medicine is available, the patient may "believe" that the medicine will save, him, but he must also act and take the medicine to be healed. You see, there has to be an act of the will to decide to take the medicine. The same holds true in the spiritual realm. The "medicine of salvation" has been provided in the life, death and resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ. We can be saved if we respond in faith to Christ's invitation to believe on Him.

Some years ago, the story was told of a missionary who was translating the Bible into the language of a certain tribe. He couldn't seem to find just the right word to describe what it means to "believe" on Christ. One day, as he was struggling to translate John 3:16, a man appeared at this door to talk about this new faith with the missionary. As they talked, the missionary asked his new convert what he thought was the best way to translate the word "believe" into his own language. The man thought for a moment and said: "I think the best way to describe the word "believe" would be to say, "to sit down." Puzzled, the missionary asked him to explain. He replied, "you are sitting on a chair. Therefore, you must believe the chair will hold you." The missionary translator caught his meaning and quickly translated John 3:16 as follows: "For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten son, that whosoever sits down on (believes on) Him should not perish, but have everlasting life."

Isn't that the true meaning of faith, to place the weight of our soul's eternal destiny upon Christ? In other words, true faith relies upon the promise of Christ that He will save us if we entrust our soul to Him. Just as a drowning man needs to entrust himself to the lifeguard to be rescued, so we too must lie still in the arms of Christ, not trying to save ourselves, but trusting Him to do the work of saving us.

Dear reader, have you entrusted your soul's eternal destiny to the Lord Jesus Christ? I said above that it is possible to believe something is true, but not act upon it. It is the same with our eternal salvation. Many believe in their minds that Jesus is Lord but do not act upon that belief. There must come a time, in each of our lives when we make the decision to ask the Lord to save us and take Christ into our lives. Have you done that? Why not do it now and pray the following prayer with faith:

Lord Jesus, I have sinned and have not lived my life for you and I ask you to come into my heart and forgive my sins. I believe that you died on the cross to save me and I ask you to make me your child. Come into my heart, Lord Jesus! I believe your promise that if I would trust in you that you would save me. I now commit my life to you. Thank you, Lord Jesus, for hearing my prayer. Amen.

If you meant that prayer from the bottom of your heart, God has heard you. Jesus said: "The one who comes to me I will by no means cast out" [John 6:37]. In other words, if you come to Christ, He will not turn you away. He must keep His word for God cannot lie. You can be assured that our Lord will keep His word and cleanse you from every sin and make you His child.

Having taken this step, the step of following Christ, don't try to do it alone. Come and join us. . . (in the church), where the strength of fellowship with others will help sustain you in your new faith.

If you have not been baptized, speak to the priest about it. Jesus said: "He who believes and is baptized shall be saved" [Mark 16:16]. If you are a church member but have been lax in following Christ, renew your baptismal vows today and enter into that personal relationship with Him.

Consecrations

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Tuesday, June 12, 2012 at 12:00AM

Tuesday, June 12, 2012 at 12:00AM Consecration of Damien Mead as the Bishop of the Anglican Catholic Church's (ACC) Diocese of the United Kingdom, and consecration of the Anglican Church of the Epiphany (ACC) by The Rt. Rev. Denver Presley Hutchens, retired Bishop Ordinary of the Diocese of New Orleans and presently Episcopal Visitor and Vicar Capitular to the Diocese of the Holy Trinity.

Is Traditional Anglicanism Calvinist or Arminian?

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Sunday, June 10, 2012 at 06:28PM

Sunday, June 10, 2012 at 06:28PM Edit, 9/8/2024:

Since I posted this 12 years ago, my thought on this matter has changed somewhat. Today I view the God's sovereignty/human volition conumdrum as quite irresolvable, both true, but a paradox that we simply have to live with. See also:

_______________________________________________

The answer to that question depends upon whom you ask. There are Calvinistic Anglicans who, pointing to a term commonly used to describe Anglicanism, "Reformed Catholicism", place the emphasis on "Reformed" and will correctly note the role the Swiss Reformation played in the thinking of Anglicanism's original divines, such as Thomas Cranmer. These Anglicans tend to be found in "low church" denominations such as the Reformed Episcopal Church and in the Evangelical wing of the Church of England. Anglo-Catholics on the other hand play down the Reformation, play up the late Caroline, Oxford and Ritualist Movements and stress the Anglican tradition's medieval Catholic roots. The "Old High Churchman" curses both camps and celebrates high Catholic ritual and Catholic church order while at the same time owning the Protestant roots of the Church of England and her daughters throughout the world. Old High Churchmen tend to be Arminian (though not in the exact way the Remonstrants were Arminian), but there have been Calvinists among them, such as Archbishop of Canterbury John Whitgift.

Certain Anglican writers have mentioned the "Pelagian" tendency of the British people (Pelagius himself was from the British Isles), and it shows up in Anglicanism, rather paradoxically, in both the conservative High Church/Anglo-Catholic types on the one hand and liberal Anglican Protestants on the other. Anglican theologian C.B. Moss notes, for instance:

(Pelagianism) is very attractive to the ordinary man of independent will and common-sense religion and morals; and particularly to the Englishman. Probably 90 per cent of the English laity (that is, practising members of Christian congregations) are unconscious Pelagians. (The Christian Faith: An Introduction to Dogmatic Theology, p.155)

Theologian W. Taylor Stevenson agrees:

While it may be of very limited historical import, it is certainly appropriate that the only heresy associated traditionally with Britain is that of the British (or Irish) monk Pelagius (active 410-418) who argued that the individual, apart from divine grace, makes the initial and fundamental steps toward salvation. That is a practical, a 'sensible' idea. It is more significant historically, and quite in keeping with the English ethos, that English piety and theology has had a an earnest Pelagian flavour extending from the Puritanism of the seventeenth century through the Evangelical movements of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. ("Lex Orandi - Lex Credendi", The Study of Anglicanism, p. 192)

One often hears the argument from Old High Churchmen and Anglo-Catholics that since "God gave us free will" and desires all men to be saved, Christians become Christians by an act of their will as they respond positively to the Gospel, and likewise persevere as Christians by an exercise of holy volition (or not persevere, as the case may be, by an exercise of unholy volition). C.S. Lewis can be cited as one notable individual who held to this view.

The rub, of course, is that to the extent that such a belief is Pelagian, it is heretical. Pelagianism was condemned not just at the local Council of Carthage in 418, but at the ecumenical Council of Ephesus in 431 as well. Anti-predestinarianism did not suddenly evaporate, however, and a view later arose that avoided certain fundamental teachings of Pelagius while maintaining the free will doctrine. This view is called Semipelagianism, and while it was condemned at the Second Council of Orange in 529, it was never condemned at an ecumenical council, as Pelagianism was. Moreover, anti-Augustinianism (of which Semipelagianism is one variety) remained prevalent in the East and in some places in the West, so the free will doctrine survived intact as a fundamental Christian theologoumenon in much of the church.

But even the anti-predestinarian Old High Churchman Moss sees a continuing danger here. Quoting N.P. Williams, he writes (parenthetical comments mine):

Pelagianism is "fundamentally irreligious, so far as it tends to destroy in the heart of man the feeling of childlike dependence on his Maker" (presumably a reference to man's salvation). We have not got the unlimited power of free will asserted by Pelagius; man is weaker and more vicious than that sheltered monk knew (to which the Augustinian and the Calvinist say, "Amen"). The discoveries of Freud (and others), even though we accept them with great qualifications, at least show that there are vast depths of evil in the subconscious mind of man, of which he is usually quite unaware (to which the Augustinian and Calvinist again say, "Amen"). (The Christian Faith, p.155)

Does it follow from any of this, however, that the Calvinist system must be accepted? Only Calvinistic Anglicans would say that it does. Most traditional Anglicans would not say so, however. The only things they must say are that 1) Pelagianism is heretical and 2) the notion that the human will is situated neutrally between good and evil and therefore is always perfectly and arbitrarily free to choose one or the other is both empirically suspect and lacks clear scriptural support.

Moss affirms, correctly in my view, that "antinomy" marks much of what is affirmed theologically in the Bible. An antinomy is an apparent paradox, "two sides, which cannot be fully reconciled by reason." (The Christian Faith, p. 49.) While I personally lean Augustinian as do many Anglicans, I do so because I think Augustine's theology more accurately reflects the soteriology of the New Testament, and especially Pauline soteriology. In a nutshell, that soteriology is this: we do not become Christians, or stay Christians, due to our own power. God must graciously make us Christians, which is to say that faith is a gift, not something we exercise naturally. Our coming to faith in Christ is quite supernatural, actually. Some representative texts from St. Paul (bolded emphases mine):

And you hath he quickened, who were dead in trespasses and sins; herein in time past ye walked according to the course of this world, according to the prince of the power of the air, the spirit that now worketh in the children of disobedience: Among whom also we all had our conversation in times past in the lusts of our flesh, fulfilling the desires of the flesh and of the mind; and were by nature the children of wrath, even as others. But God, who is rich in mercy, for his great love wherewith he loved us, even when we were dead in sins, hath quickened us together with Christ, (by grace ye are saved;) and hath raised us up together, and made us sit together in heavenly places in Christ Jesus: That in the ages to come he might shew the exceeding riches of his grace in his kindness toward us through Christ Jesus. For by grace are ye saved through faith; and that not of yourselves: it is the gift of God: Not of works, lest any man should boast. For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus unto good works, which God hath before ordained that we should walk in them. (Eph. 2:1-10, KJV)

Wherefore, my beloved, as ye have always obeyed, not as in my presence only, but now much more in my absence, work out your own salvation with fear and trembling. For it is God which worketh in you both to will and to do of his good pleasure. (Philippians 2:12-13, KJV)

And St. Augustine's favorite text:

. . . and what hast thou that thou didst not receive? now if thou didst receive it, why dost thou glory, as if thou hadst not received it? (I Cor. 4:7, KJV)

However, I am unwilling to draw certain of the same conclusions Augustine and some of his followers (especially the Calvinists) did. It is quite clear from the New Testament, against the Calvinists and against certain things that even Augustine seemed to say concerning the limited scope of the atonement, that Christ died for all men and that God therefore wills the salvation of all men. But that does not commit me to a Pelagian, Semipelagian or Semipelagian-like conclusion that God has given all men free will (defined as an uncaused cause of human behavior) and looks nervously down from heaven to see who among these "all" will take Him up on his offer and who will not. There very well may be other theological options.

However, it's a difficult theological area to be sure. Ignoring the phenomenon of antinomy in the Bible and accordingly trying to boil down rationally the predestinarian or the voluntarist theology tends to land us in trouble. But that doesn't mean we don't have a clear choice to make. Augustine scholar Gerald Bonner summarizes the argument of the Anglo-Catholic theologian J.B. Mozley (again, bolded emphasis mine):

In a study of Augustinian predestination first published in 1855, J.B Mozley, brother-in-law of John Henry Newman and later Canon of Christ Church, Oxford, and Regius Professor of Divinity, theologically orthodox but fair-minded and aware of the limitations of the human intellect, noted the ideas of Divine Power and human free will, while sufficiently clear for the purposes of practical religion, are, in this world, truths from which we cannot derive definite and absolute systems. "All that we build upon either of them must partake of the imperfect nature of the premise which supports it, and be held under a reserve of consistency with a counter conclusion from the opposite truth." The Pelagian and Augustinian systems both arise upon partial and exclusive bases. Mozley held that while both systems were at fault, the Augustinian offends in carrying certain religious ideas to an excess, whereas the Pelagian offends against the first principles of religion: "Pelagianism . . . offends against the first principles of piety, and opposes the great religious instincts and ideas of mankind. It. . . tampers with the sense of sin. . . . (Augustine's) doctrine of the Fall, the doctrine of Grace, and the doctrine of the Atonement are grounded in the instincts of mankind." (Freedom and Necessity: St. Augustine's Teaching on Divine Power and Human Freedom)

In other words, to paraphrase Mozley, it is better to err in the direction of St. Augustine than Pelagius. Augustine is a saint and Doctor of the Church, and widely regarded to be the greatest of all the Church Fathers; Pelagius is a heretic and the Semipelagians have been more or less judged by the Church to be the bearers of errant doctrine. Augustine points us to the hope of grace, Pelagius to the hopelessness of free will and works salvation. Augustine, following St. Paul, taught that the will was not free without grace, and even then needed the constant assistance of God's grace to choose daily to live the Christian life. Salvation is not by works, but grace. If anything is clear from the New Testament, it is that. But we must be careful about what conclusions we draw from all this. Most Anglicans are thus careful, and so when they are asked whether traditional Anglicanism is Calvinist or Arminian, they will answer with a deliberate and clear "yes."

That's our story, and we're sticking to it.

Ergo: the potential Evangelical convert to traditional Anglicanism who happens to be on the Reformed side of things should not be put off by Anglican anti-predestiniarianism. The Augustinian (and in some churches, the Calvinist) doctrines of grace are held by a goodly number of Anglicans. Whether the anti-predestinarian Anglicans want to admit it or not, Augustinian soteriology is an acceptable theologoumenon in the Continuing Anglican Church, just as it is in the Roman Catholic Church. And the Arminian Evangelical who joins Anglicanism will be welcomed with many open arms, including those of old St. Clive himself.

How I Got There: An Evangelical Converts to Anglicanism

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Thursday, June 7, 2012 at 09:10AM

Thursday, June 7, 2012 at 09:10AM Part I

It’s been said that a paradigm shift occurs for one of three reasons: 1) a crisis situation; 2) an influential individual; or, 3) an overload of information. When I became an Anglican, all three of these influenced my decision.

In 1989 I graduated from Dallas Theological Seminary (ThM) and became the pastor of a Bible Church in North Dallas. At that time, I knew nothing of Phillip Schaff and his subtle diagnosis of American Protestantism.

"Tendencies, which had found no political room to unfold themselves in other lands, wrought here without restraint. Every theological vagabond and peddler may drive here his bungling trade, without passport or license, and sell his false ware at pleasure. What is to come of such confusion is not now to be seen (The Principle of Protestantism, Phillip Schaff, 1844)."

One hundred-forty-five years after Schaff penned those prescient lines, I not only saw what he predicted, I experienced it. When I entered the pastorate my priorities were to teach God’s Word and to shepherd God’s people, but the congregation that called me was a loose confederacy with no system of doctrine to galvanize it. In addition, its growing number of programs demanded an administrator, not a preacher.

During this pensive season, I lingered over the Protestant visage. I read her magazines and journals. I listened to her music. I watched her television programs. I wasn’t a participant, but a curious observer.

What I witnessed still baffles me. Her children lumbered to Weigh Down and bought t-shirts emblazoned with, "Food Cannot Meet My Needs." They loaded onto busses and headed to Promise Keepers where they cried and vowed to burn their Swim Suit edition of Sports Illustrated. Then they spent the night on the sidewalk to be the first in line to purchase The Prayer of Jabez, a book that promised to change their lives.

From where I was standing, much of the Protestant Church looked like a lab rat in a maze, frenetically searching for the next, new experience. Its appetite was insatiable. Nothing satisfied. Nothing lasted. Nothing remained the same. It couldn’t remain the same, or its children would get bored and boredom was a sin.

I was on a journey, and the Protestant path had led me to a wasteland where God was trivialized and His Church was marginalized. I remember writing in my journal, struggling to describe the shift that was taking place inside of me. From the walls of my study, the ink portraits of Hodge, Calvin, and Edwards watched quietly.

But they had no answers.

My heart was hungry for something more than barren sanctuaries, long lectures, and prayers during worship that were made up on the spot and for the most part were bereft of serious forethought, Scripture and theology.

A. W. Tozer, a respected Evangelical of the earlier part of this century wrote the following. "We of the non-liturgical churches tend to look with disdain upon those churches that follow a carefully prescribed form of service . . . The liturgical service is at least beautiful; ours is often ugly. Theirs has been carefully worked out through the centuries to capture as much of the beauty as possible and to preserve a spirit of reverence among worshipers. Ours is often an off-the-cuff makeshift with nothing to recommend it. In the majority of our meetings there is scarcely a trace of reverent thought, no recognition of the unity of the body, little sense of the divine Presence, no moment of stillness, no solemnity, no wonder, no holy fear." (God Tells the Man That Cares, A.W. Tozer)

And this is what my heart craved - the solemnity, stillness and wonder described by Tozer. I was searching for serious worship and a sacramental life that would immerse me in the life of the Holy Trinity.

It was during this period that I asked myself, "Is my faith something I invented? Or, is it the faith of the prophets, the apostles, the Early Church Fathers and the martyrs? How can I know?"

It dawned on me that I was sitting in judgment of the historic Church. I had annointed myself the final arbiter of what was orthodox doctrine and worship. I alone had decided what I would believe and how I would worship. I was shocked to find that I looked a whole lot like the folks I had been watching!

In 1990 my children were baptized and my family became Anglican.

Part II

After last week’s post, I received an email from a friend, who wanted to know why I converted to Anglicanism. He pointed out that my post didn’t explain my reasons for ambling down the Canterbury Trail. Here is an edited copy of my response to him. Proverbs 27:17 “As iron sharpens iron, so one man sharpens another.”

Dear ______________:

Thank you for your response to last week’s blog post, “How I got Here from There: My Conversion to Anglicanism.” Your queries caused me to pause and ponder again the beauty of Anglicanism and how God drew me to her. You didn’t ask for a lengthy explanation like this. In fact, you asked to visit over coffee, or scotch – an offer I still plan to take you up on.

I wrote this for two reasons. First, I wanted to revisit and savor what happened to me 20 years ago. Second, I’m a firm believer in writing’s ability to sharpen wooly headed thinking.

You mentioned in your email that twenty years ago there was a mass migration from what you call “Word based” worship into more reverent, sacramental worship. You are spot on. Robert Webber chronicles this exodus in his book, Evangelicals on the Canterbury Trail. In Evangelical is not Enough, author Thomas Howard articulates why these people left. As best as I can tell, their departure wasn’t an emotional reaction brought on by an unbridled desire for aesthetics. Instead, these people wanted worship that conformed to the heavenly pattern of Revelation 5-7.

In your email you asked why I became an Anglican. I may have unintentionally mislead you in my original blog post by intimating that irreverent worship was the reason I left my roots. In fact, that is not true. My reasons for converting to Anglicanism were many.

In the early 90’s I was looking for a church that valued the Scriptures. I found it. Anglicans read (present tense) from the Old Testament, New Testament and Psalter each day during Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer. Its Lord’s Day worship includes lengthy readings from the Prophets, the Psalter, the Epistles, and the Gospels.

A perusal of the 1662 and 1928 editions of the Book of Common Prayer reveals that the Scriptures are woven into the warp and woof of every service and office. It’s been estimated that upwards to 75% of the Prayer Book is either a direct quote or accurate summary of Scripture.

During worship, Anglicans pray the Word, chant the Word, hear the Word, and eat the Word. In short, Anglican worship is saturated with the Word.

So, this is the first reason I’m an Anglican and not a Lutheran, Roman Catholic, or Presbyterian. In my estimation, Anglicanism is unsurpassed in its appreciation of Scripture.

A second reason I converted to Anglicanism is that the Anglican ethos is pastoral. Now, that’s more than a mere slogan. It’s a truth that springs from the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion.

When you have a moment, read through the Articles of Religion. You’ll notice that they take up a few pages at the back of the Prayer Book. There’s a good reason for this. The Articles of Religion outline the Christian faith in broad brush strokes, so as to create a sheepfold for all who believe the Creeds, the Lord’s Prayer and the Ten Commandments.

You’ll also find that the Thirty-Nine Articles sound as if they were written by a pastor. In fact, Article XVII was penned with a genuine concern for how people might respond to the doctrine of election. Also, couched within the Article is a pastoral admonition regarding an improper preoccupation with the doctrine of predestination.

All of that to say this - I gravitated toward Anglicanism because of its pastoral ethos, its culture of incarnational theology that vivifies truth in worship and ministry. The Ordinal of the Book of Common Prayer (1549) further illustrates this. In the past Anglican parishes were often called “Cures,” and priests were referred to as “Physicians,” who administered the “Medicine of Immortality.” Hence, when a priest was ordained, the Bishop said:

Have in remembrance into how high a dignity and to how weighty an office and charge ye are called: that is to say, to be the messenger, the watchmen, the pastor and the steward of the Lord; to teach, and to premonish, to feed and provide for His children in the midst of this naughty world, that they may be saved through Christ forever. . .

See that you never cease your labour, your care and diligence, until you have done all that lieth in you, according to your bounden duty, to bring all such as are or shall be committed to your charge, unto that agreement in the faith and knowledge of God, and to that ripeness and perfectness of age in Christ, that there be no place left among you, either for error, or viciousness of life.

Mark the incarnational and relational images. The priest is a father and the parishioners are his children. He is responsible for raising and nuturing them.

The poet-priest, George Herbert wrote the following about the pastoral culture of Anglicanism. “The country parson is not only a Father to his flock, but also professeth himself thoroughly of the opinion, carrying it about with him as fully as if he had begot his whole parish. For by this means, when any sins, he hateth him not as an officer, but pities him as a Father.”

Another reason I became an Anglican is that my study of the Scriptures and Church history convinced me that both the Word and the Sacraments are vital to worship. So, in my estimation, it’s ill advised to bifurcate between the two. It has been my experience that when false distinctions like that are made, pastors become imbalanced and to do things like preach 87 messages on John 3:16 and to spend three years expounding the Ten Commandments. It seems to me, that kind of lopsidedness feeds the Gnostic idea that worship is primarily mental. When I jumped off the Protestant ship, I was searching for worship that encompassed both the physical and the mental, the Word and Sacrament, the kind of worship found in the Book of Common Prayer.

My reasons for converting to Anglicanism are almost too numerous to number. I suppose I could cite five or six more critical issues that prompted my conversion, including Anglicanism’s historic episcopacy, and its time-tested model of spiritual formation.

I trust this note has answered your questions.

Regards,

Fr. Doug

Anglicanism: Its Past and Promise

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Wednesday, June 6, 2012 at 11:24PM

Wednesday, June 6, 2012 at 11:24PM by The Rev. Dr. Tory Baucum, Rector, Truro Church

Luther was once asked how he started the Reformation. In his characteristic florid style, Luther replied, “I did not start the reformation. All I did was preach the word of God and drink beer. The Word of God did the reforming.”

Similarly, Dr. Otto Piper of Princeton Seminary once admonished his students in this way:

We make a mistake when we think that Luther and Calvin produced the Reformation. What produced the Reformation was that Luther studied the Word of God. And as he studied it, it began to explode in him. And when it began to explode inside him he did not know any better than to let it loose on Germany. The same was true of Calvin. The tragedy of the Reformation was that when Luther and Calvin died, Melanchthon and Beza edited their works. And so all the Lutherans began to read the Bible to find Luther and all the Calvinists read the Bible to find Calvin. And the great corruption was on its way. Do you know there is enough undiscovered truth in the Bible to produce a Reformation and evangelical Awakening in every generation, if we only expose ourselves to it until it explodes in us and we let it loose?

Anglicanism shares in this larger movement of reform. It began as an indigenous reform movement of the 15th and 16th centuries that was let loose by Latimer, Ridley, and Cranmer, but was co-opted by a politically opportunistic King (something, of course, that never happens in our age!).

Despite this checkered beginning, Anglicanism remains a reform movement within the larger body of Western Christendom. In subsequent centuries it has spawned smaller reform movements such as the Wesleyan revival in the 18th century, the Oxford movement in the 19th century and most recently the Alpha movement in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Each of these Anglican renewal movements has three defining doctrinal emphases, which together constitute the full power of Christian salvation: original sin (everyone needs a Savior, not just a coach), justifying grace (such a Savior and His salvation has been given to us without our merit) and sanctifying grace (the salvation that is offered to us is transformational, not merely transactional. That is, it must be personally and continually appropriated). The surface differences between Methodism, the Oxford movement and Alpha should not obscure this shared Anglican doctrinal DNA.

Like the other Protestant reformers, Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer, was a Catholic who yearned to see the Medieval Church reformed according to these three-fold emphases. The Church of England, like the Reformation churches in Europe, was simply an attempt to re-Christianize Christendom by reintroducing to the Church the full power of Christian salvation.

The reformer’s goal was making new Christians, not Cranmerians nor even Lutherans or Calvinists. Where the various Reformation Churches differed was in the strategy and tactics they employed to achieve this common goal of re-Christianization.

Somewhere else, I have explained the relationship between Anglicanism and the Reformation Churches:

Anglicanism was an indigenous reform movement which shared many features of the Continental reformation: gospel liberty, biblical literacy and ecclesiastical downsizing. At its early stages, the reform was a synthesis of Erasmus’ strategy of learning and Bucer’s concern for parish-based discipline, both of which were grafted onto Luther’s rediscovery of justification by faith as the root transaction between God and humans. This discovery of Luther was due, in part, to his rediscovery of Augustine’s doctrine of grace…A variety of scholars were stimulated to a new perception of Augustine by the first scholarly printed edition of his work which began to appear in the late 15th century. The impact of this discovery cannot be overemphasized.

This common patrimony in Augustine is an essential part of our Church’s identity. In his 1562 defense of Anglicanism, “Apology of the Church of England,” John Jewel relied extensively on the Fathers but quoted St. Augustine far more than any other Father of the Church to make his case. We Anglicans highly esteem the Bible as the Word of God, the norm of Christian faith, but we Anglicans also know the Bible cannot be read in a vacuum.

Everyone reads the Bible from some standpoint or tradition. Anglicans acknowledge, up front, that we read the Bible through the lens of the early Church. And Augustine was the epitome of the early Church. It is not an overstatement to say that Anglicans are essentially reformed Augustinians, keeping original sin, grace and sanctification as the integrating touchstones of our doctrine of salvation.

This reformist character of Anglicanism - defined by its Augustinian interplay of original sin, grace and sanctification - not only outlines our historical beginnings, but also illumines how modern Anglicanism “got off the rails” in North America.

The Episcopal Church spawned two quasi-theological movements in the past two centuries: Liberalism in the 19th century and the Charismatic renewal in the 20th century. Unfortunately, neither Liberalism nor Charismatic renewal rotated entirely around this Anglican theological universe.

Liberalism upheld grace, but neglected (and sometimes outright denied) original sin and sanctification. The Charismatic renewal upheld original sin and sanctification, but often neglected grace (especially in its justifying phase). Each generated its own constellation of theological shooting stars but neither illuminated the full power of salvation. Thus, neither was evangelistically fruitful.

American Christendom was not re-Christianized by the Episcopal Church. I believe the new Province of Anglicanism must appropriate the theological heritage outlined above in order to fulfill its full redemptive potential. American Christendom needs to be re-Christianized. At our best, we Anglicans are a reformed and reforming movement of Catholic Christians, devoted to the historic faith and practice of the early church.

We possess both a form (sacramental Christianity) and meaning (evangelical Christianity) that speaks to the anomie in the post-modern American soul. It is now time to thoughtfully reengage the Word of God until that Word explodes in us and we simply “let it loose” in North America. If we do, I would not be surprised to see the next Great Awakening emerge from within our communion of Churches.

Celebrating 400 years of Anglicanism in America at the Old Jamestown Church

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Wednesday, June 6, 2012 at 01:41AM

Wednesday, June 6, 2012 at 01:41AM Welcome to The Old Jamestown Church

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Tuesday, June 5, 2012 at 02:31AM

Tuesday, June 5, 2012 at 02:31AM A blog written by me.