The Church Calendar

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Sunday, December 1, 2013 at 07:00PM

Sunday, December 1, 2013 at 07:00PM

An excellent video from Christ Church Anglican. H/T wyclif.

Take An Hour, Sit, Pray, Contemplate, Relax. . .

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Thursday, November 14, 2013 at 09:53PM

Thursday, November 14, 2013 at 09:53PM and listen.

Bishop-Elect Stephen Scarlett Consecrated Bishop Ordinary of the ACC's Diocese of the Holy Trinity

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Friday, November 1, 2013 at 08:12PM

Friday, November 1, 2013 at 08:12PM Press release here. All I can say is, good for DHT, which has been without a bishop ordinary for quite awhile.

This could also auger well for the ACC, as St. Matthew ACC in Newport Beach is a "Prayerbook Catholic" parish that has become something of a flagship for the ACC. Perhaps Scarlett and St. Matt's will use their stature in the province to either reverse or halt the hardline Anglo-Catholic direction in which it currently is moving. Yes, I know it probably won't happen, but I reserve the right to fantasize.

Happy Feast of All Saints

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Friday, November 1, 2013 at 12:23PM

Friday, November 1, 2013 at 12:23PM And yes, Messrs. Sm and Frost, I see you. I'll attend to you soon. ;)

New To The Blogroll: The Low Churchman's Guide to the Solemn High Mass (Humor)

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Wednesday, October 30, 2013 at 02:41PM

Wednesday, October 30, 2013 at 02:41PM "The Gospel Transforms or It Is No Gospel."

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Thursday, October 24, 2013 at 12:16AM

Thursday, October 24, 2013 at 12:16AM The Most Rev'd Peter F. Jensen, D.Phil. (Oxon.) (H/T Drew Collins)

“A Vision for St. Stephen’s”

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Tuesday, October 22, 2013 at 01:00AM

Tuesday, October 22, 2013 at 01:00AM What he said. It should be every classical Anglican's vision.

Anglican Realignment,

Anglican Realignment,  Anglican Spiritual Life,

Anglican Spiritual Life,  Book of Common Prayer,

Book of Common Prayer,  Church Planting,

Church Planting,  Contemporary Christian Worship,

Contemporary Christian Worship,  Eastern Orthodoxy,

Eastern Orthodoxy,  English Reformation,

English Reformation,  Eucharist,

Eucharist,  Evangelical and Catholic,

Evangelical and Catholic,  Evangelism,

Evangelism,  Reformed Episcopal Church,

Reformed Episcopal Church,  Roman Catholicism,

Roman Catholicism,  The Gospel,

The Gospel,  Traditional Anglicanism,

Traditional Anglicanism,  Why Anglicanism?

Why Anglicanism? On Leaving the Episcopal Church

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Tuesday, October 1, 2013 at 11:41PM

Tuesday, October 1, 2013 at 11:41PM Fr. Jonathan over at The Conciliar Anglican has made a fine pitch, as fine a pitch as could be imagined, for Anglicans staying in the Episcopal Church. I recently had a brief discussion with my friend and fellow blogger Jordan Lavender (The Hackney Hub) over this very issue. (He would agree with Fr. Jonathan.)

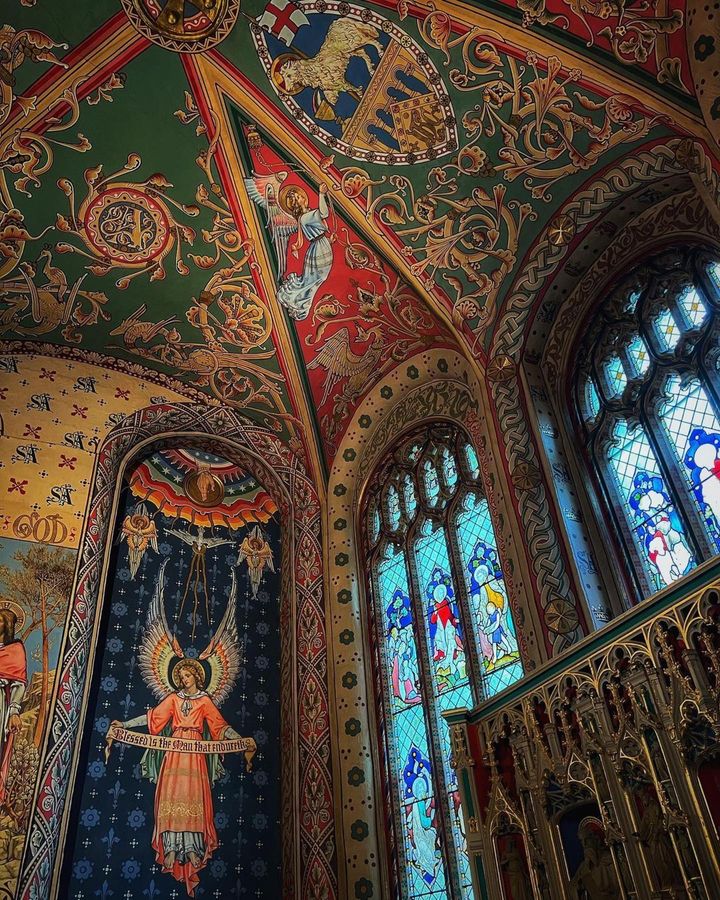

If only I could be persuaded. TEC enjoys the longest Anglican legacy here in America and owns some of the finest Christian edifices around. But I cannot, and that for essentially the same reasons set forth by a commenter who goes by the handle "With You In Spirit." I post his comments to Fr. Jonathan's blog article in their entirety:

My wife and I recently left the Episcopal church, during of all things, confirmation. Our departure stemmed from a longstanding clash of personalities with the local vicar, though the clash could also be seen as generational.

I had attended this church for a decade, and it was there I married my wife. My wife and I spent months reading scripture and performing daily devotions using the 1928 prayer book in preparation for confirmation. We lit candles and performed the full morning and evening services on waking and before bed. The routine was tough. During confirmation classes we mentioned our use of the 1928 prayer book and the vicar’s response was dismissive and flippant: “if *I* prayed from the older prayer book *I* would attend another church, probably Methodist”. Immediately afterwards, the vicar issued a patronizing lecture on the importance of women’s rights completely unrelated to anything we had been discussing in class, and my wife, exasparated, told the vicar that as a women what he was saying was both unnecessary and unneeded. What followed was a ten minute lecture on Hooker’s theory that the church rests on three legs, and the leg which we were deficient in was reason. As he spoke I recall his Starbucks coffee cup trembling. With no break in his lecture he ended class early and walked us and the other attendees out of the church, addressing us the whole time, stating how he knew plenty of conservative in the church, and “though he disagreed with everything they stood for”, he supported their freedom of speech.

For clarification, my wife is a member of a teacher’s union and I consider myself a protectionist democrat, though we never bring up our politics at church.

My wife and I attended church the following week and the vicar attacked us in the sermon, portraying us figuratively as “those who would exclude”, darting eyes, and drawing snickers from the pews. In the same sermon he cited me by name in a rhetorical example, “it would be as if went around town behaving as if he wern’t a Christian then said he was a member of our church”. We walked out during the service and have not returned.

And I don’t know why we would. My wife and I read about Spong, Schori, and the other clergy currently held in reverence and we find that we have little in common with either their beliefs or aims. To use women’s rights as an example, as average Generation X-ers with a desk jobs, we have more female supervisors and coworkers than their male counterparts, and thus the ’60s femanist dialectic just doesn’t wash, and certainly doesn’t lead us closer to Jesus. The feminist and gay rights “issues” were solved by Jesus 2000 years ago when he told us to turn the other cheek. Unfortunately, the church appears desparate to magnify and heighten greivences rather than teach others be at peace. Rather than directing people away from their passions the church is mired in the language of social justice and critical theory. The hatred of tradition espoused by the current generation of church leadership is at times bewildering: apparently an Episcopalian worshipping from the 1928 prayer book should leave the church, while in that same church Episcopalians are expected and encouraged to celebrate the Jewish Seder. If one disagrees they can expect to be fillibustered and attacked in sermon, usually through blindingly hypocritical appeals to progress and tolerence.

It just got to be too much for us. As two of the youngest members of the church we hoped that we could “hang in there” until the current generation in power moved on, but of course that didn’t happen. The wife and I are part of a generation that seems destined to endure the Baby Boomer’s tantrum against the past, and we found we just don’t have the patience. The Silent Generation are meekly enduring the politics of their nephews during their final decades, while the Boomers seem to be either in the clergy basking in the limelight or absent altogether. The alphabet generations would rather play their video games than listen to their parents politics on Sunday. The pews are empty, and one must ask what exactly separates the morals of MTV from the morals of the modern Episcopal church? If they are both the same, why show up? And if the church is going to become active in social issues, why not address those which the average person actually comes in contact with daily, such as rampant usury, ever-expanding payday loan rackets, a culture educated to illeteracy by television, a widespread contempt for manners and etiquette, casual defimation of Christianity in the media, education an healthcare treated as a business opportunity, automation and thoughtless “progress” destroying trades faster than they can be learned, and a unquestioned reverence for reductionistic science. Again, why parade out the St. Rosa Parks in 2013? Move on, get over it, or better yet, rise above politics altogther and focus on Jesus, the apostles, and the saints. Teach people how to make prayer a ritual and thereby escape from an increasingly fickle and inhuman world to something that endures.

So where did we go? You’d never guess. When the vicar wasn’t incorporating references to the Rolling Stones or sports trivia in his sermons he was slandering Baptists. Sure enough, we took it as an endorsement. While we are still adjusting to the karaoke choir and powerpoint projector screen, we have found levity and laughter …though we still do our daily devotionals and read our scripture from Knox.

Peace be with you, remaining Episcopalians. May you be stronger than us.

In a follow up response to a commenter who objects to Baptists, With You In Spirit wrote,

When we decided to leave our church we weren’t sure where to go. We have no continuing Anglican churches less than three hours away, unfortunately. We would definitely attend if one were local. I had attended a Missouri Synod service in town some years ago and liked the people there, however, the church suffered terribly from modern aesthetics. The LCMS church used plastic communion cups, had stark florescent lighting (~6500K), a drop-tiled ceiling, used banquet chairs in lieu of pews, etc. This was not for want of money either, rather, the church was a larger congregation that just seemed to prefer the efficiency-expert touch. Attending the church felt like worshiping at Wal-Mart. The same can be said for the other churches we’ve visited over the years, whether Methodist or Lutheran: plastic plants and projector screens. We even tried the Catholic church and were surprised by the kitschy 70′s hymns being accompanied by a Casio keyboard replete with a MIDI drum loop. Lord, how we miss the aesthetics of the Episcopal church!

Anyway, the walk to our old church regularly took us past the Baptist church previously mentioned. Based on the “endorsements” of the vicar, we stopped in one Sunday and were amazed by the friendliness. We now regularly visit the pastor and his wife at their home have long talks on the porch. Occasionally we even disagree, but amazingly, the disputes never became bitter as was the case with our vicar.

While I’m no expert on Church history, I have read through Augustine and have spent time with the 39 articles of the BCP and hope to have an understanding of the importance of catholic faith. That being said, I do not believe that the hierarchy of the Church is steered infallibly, or, that God is incapable of abandoning certain churches or even entire denominations if those denominations become corrupt. Paul warned the early churches in his epistles because those warnings served a purpose; churches are fallible and thus perishable. Moreover, at some point even the act of attending an errant church signals an endorsement, and frankly, the insincere and pompous seminary graduates we’ve met seem more deluded than many of the straightforward and humble Baptists we’ve recently become acquainted with. Erasmus’ Praise of Folly critiques “learned fools”, and so too is there something comforting in the laconic honesty of Baptists when set aside the politically correct sophistry which passes for wisdom among the current Episcopal clergy. Such people seem more concerned sounding good rather than actually being so. Anyway, we considered our departure a vote with our feet. If that makes us Donatists, then so be it.

At this point we’re over the branding of the various denominations. Christians are what they do, not what they label themselves, and being a Christian certainly involves more that being “up” on the latest thoughts and opinions that are in fashion. We gave up on television years ago and the last thing we want to be subjected to on Sunday is a return to regularly scheduled programming. I still consider myself an Anglican in spirit in that I worship from the prayer book and prefer the older traditions of the church, but when publicly worshiping I’ll go where I hear laughter, readings from the bible, and common sense. This is likely what my wife thinks as well. We’ll be praying for the Church and hoping for the best.

Peace be with you all.

Having spent several months in PECUSA (now TEC) back in 1983-1984 and watched TEC's devolution since then from afar, I must say that I wholeheartedly track with his and his wife's reasons for leaving. If I were in his shoes I'd do much the same thing, though I would seek out those individuals living close by who would love to get together to say Morning and/or Evening Prayer with us. And that, being a place where two or three are gathered, would be the nucleus of an Anglican house church. We could perhaps attend an area Evangelical church for sermon support and wider fellowship, and receive communion at the local TEC parish without having to make any kind of commitment to it. Necessity is the mother of invention.

And who knows? From there we might get episcopal oversight from a bishop in a Continuing or Realignment church and eventually maybe even a priest. But regardless, we'd be living in community centered around the BCP, a veritable "Little Gidding". That would be enough, if you ask me.

Making Men Out of Boys

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Thursday, September 26, 2013 at 04:41PM

Thursday, September 26, 2013 at 04:41PM Tarsitano: Of Forms and the Anglican Way

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Thursday, September 26, 2013 at 01:50AM

Thursday, September 26, 2013 at 01:50AM Roger Salter on "Three Streams" Anglicanism

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Monday, September 23, 2013 at 02:01PM

Monday, September 23, 2013 at 02:01PM I continue to watch this debate with interest. From Salter's most recent VOL article:

"Three Streams" is a compromising and confusing attempt at synthesizing three divergent theologies that maintained in their integrity cannot be combined. In English nomenclature variant churchmanships cannot be united. Respected yes, but not rolled together in one. Merely to cite similarities in thought and experience is not sufficient to establish confessional agreement and honesty (integrity). Each must be true to its core convictions and these are incompatible. By all means insights will be gained from each other. Men of the Word see it confirmed and dramatized in the Sacraments (Luther says there is greater power in the word than in the sign: The Babylonian Captivity of the Church). Men of the Word know and rely upon the Spirit who spoke by the prophets.

Men of the Word attribute great influence and wonders to the ministry of the Spirit. These things are shared across the board. But they need not share the theological conclusions of Anglo-Catholicism or Charismaticism. Word, Sacrament, and Spirit are utterly depended upon, but not necessarily the deductions arrived at by all fellow Christians who nonetheless may be held in affection and admiration. Christian unity does not have to be achieved in watertight visible form but in love for Christ and our fellows. Caution and carefulness in theology is not to be identified with prejudice (contend for the faith that was once for all entrusted to the saints - Jude v3). Testing the claims and phenomena of Charismaticism does not consign anyone to the "frozen chosen" (try the spirits, whether they are of God - 1 John 4:1). . . .

Three Streams is hardly the"big deal" it pretends to be and it is an unnecessary superficiality as any grasp of Historical Theology would discern. Again, what "orthodox" version of Christian faith omits to recognize Word, Sacrament, and Spirit? But what responsible theology would attempt to blur the real distinctions between full-blooded Evangelicalism, outright Anglo-Catholcism, and enthusiastic Charismaticism? Views on soteriology, sacraments, and the Spirit's manifestations are too important to gloss over with a cheap formulaic construction (Three Streams) that covers vital differences (how Christ is grasped? what is the nature and effect of the sacraments? what are the marks of the Holy Spirit, or the expression of the human spirit - good or bogus - in religious experience? Three Streams is an ecclesiastical commercial slogan for a Christian coalition that sacrifices integrity. To add a personal note, I have benefited enormously from Anglo-Catholic and Charismatic associates and authors. I have thrilled to a variety of liturgies in a number of ministerial situations. I am not an antiquarian for the sake of being one. I am impressed by the heritage bequeathed to us from twenty centuries of Christian witness but I also detect the drift from our moorings and the rectification requires the historical perspective wedded to responsible theology in our time and I'll ransack any generation of Christian endeavour to that end. Heritage guides the here and now and to blithely say lets just stick to the Bible overlooks that we come to Scripture with our own presuppositions and ducks the issue as to whether our hermeneutic is viable. We are part of the church's testimony and not our individualistic interpretations.

Bad Charismatic Habits

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Monday, September 23, 2013 at 12:10PM

Monday, September 23, 2013 at 12:10PM Having given my charismatic brothers in Christ a rose (and complementing a response I gave to Alice Linsley here), I wish to now draw their attention to the thorns:

While I appreciate the author's intellectual honesty, my impression is that the bad habits number more than just nine. This morning I encountered the argument of a woman on an Anglican discussion board that went as follows (and I paraphrase): "We must accept the practive of women's ordination to the priesthood because my pastor (a woman ordained in the ACNA) received a 'word of knowledge' from someone that she was to become a priest, and oh, by the way, these days we recognize the equality of men and women."

Now, when such private revelations have the effect of sweeping away in one "word" of supposed "knowledge" both the practice of the apostles and the 2,000-year practice of the one, holy, catholic and apostolic church, we can be pretty sure that the spirit of false prophecy St. John enjoins us in I Jn. 4:1 to vigilantly discern what was at work in this woman's supposed call to the priesthood. And if Anglicans are going to continue to say the Apostles' and Nicene Creeds with integrity, and thus profess their belief in the Catholic Church, then they will need to fully embrace the English Reformers' devotion to Her. As Anglican blogger Death Bredon has succinctly put it, "Anglicanism can, perhaps uniquely, lay equal claim to the appellations Protestant and Catholic and affirm both without any sense of inconsistency or incoherence. Indeed, strictly speaking, in proper understanding of each term, to truly be one, you must be both."

The point is that charismatics, and especially Anglican charismatics, are going to have to shed a number of their their wild and woolly ways -- or "bad habits" -- if they ever want to join the mainstream of Evangelical Catholicism.

What Worship Is For

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Thursday, September 19, 2013 at 08:20PM

Thursday, September 19, 2013 at 08:20PM Why Men Don't Sing In Church

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Wednesday, September 18, 2013 at 03:49PM

Wednesday, September 18, 2013 at 03:49PM The Day Thou Gavest Lord Is Ended : The Choir of the Abbey School, Tewkesbury

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Wednesday, September 4, 2013 at 11:05PM

Wednesday, September 4, 2013 at 11:05PM One More For Good Measure

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Monday, September 2, 2013 at 01:39AM

Monday, September 2, 2013 at 01:39AM I'll be posting this one again next Easter, assuming I'm still around these earthly parts. (One never knows. If not, I'll be singing it in heaven.)

Renaissance Musical Interlude

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Monday, September 2, 2013 at 01:31AM

Monday, September 2, 2013 at 01:31AM Sometimes you just gotta "motet." Know what I mean?

Addendum to "Anglicanism and the Charismata"

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Sunday, September 1, 2013 at 07:22PM

Sunday, September 1, 2013 at 07:22PM Anglicanism and the Charismata

I add here that not only should both cessationist and continuationist Anglicans be happy when charismatic Christians seek the litugical riches and stability of the orthodox Anglican tradition, they should be postively giddy when Cambridge-educated charismatics -- in this case a member of the Assemblies of God -- write such excellent treatises on liturgical theology. I am currently reading Chan's book.

Anglicanism and the Charismata

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Tuesday, August 27, 2013 at 01:08AM

Tuesday, August 27, 2013 at 01:08AM Acts 5:38-39

Over at our church's Facerbook, which I created and maintain, a certain anonymous jokester (quite possibly a Facebook friend) recommended that I add "Assemblies of God" to the "Anglican Church" subcategory I listed on the page. I suppose this is because of much of the Anglican Realignment's embrace of "three-streams" Anglicanism, which includes the charismatic stream along with Catholic and Evangelical streams. Indeed, there are many charismatics in these Anglican jurisdictions, including Anglo-Catholic ones). Our jokester wants me to own up to it, I guess, suggesting that a Realignment church is as much like an Assemblies of God church as it is an Anglican church. Not true, of course, but I rather enjoyed the wry wit before I pushed the "reject" button.

I myself have never spoken in tongues, been "slain in the Spirit", received a "word of knowledge", prophesied, or any of that. Nor do I seek any of these gifts. In the past, I have tended toward cessationism. But I long ago shed that position, and this for reasons -- as implied above -- that have nothing to do with a personal experience of any of these phenomena. Rather, I came to see that: 1) cessationism does not hold together exegetically; and 2) there's just too much anecdotal evidence that much of this -- but certainly not all -- may very well be miraculous manifestations of the Spirit's activity.

I have found support for my conclusion in the most unlikely of places. Examples from the Reformed camp, where cessationism reigns supreme, two articles by Vern Poythress:

Modern Spiritual Gifts as Analogous to Apostolic Gifts: Affirming Extraordinary Works of the Spirit within Cessationist Theology and What Are Spiritual Gifts?

and a fairly sypathetic treatment from J.I. Packer:

Theological Reflections on the Charismatic Movement, Part 1 and Theological Reflections on the Charismatic Movement, Part 2.

One can find in modern Anglican theological literature many defenses of the charismata for the modern day. Witness, for example, several excellent articles at The Continuum:

Confessions of an "Enthusiast"

A Bishop of the ACC reflects on the Charismata

In defense of Fr. Wells (Fr. Wells, a personal friend whom I esteem more that words can say, being a champion of cessationism)

Anglican Catholicism and the Charismata

The Charismatic reality of the Church

And lastly, see the exchange between Gillis Harp (a critic of three-streams Anglicanism) and Donald Richmond (a defender) here.

Now, last time I checked, neither Poythress, Hart, Kirby, nor Richmond have any connection to the Assemblies of God. That members of the Assemblies of God have become Anglican and have joined charismatic-friendly jurisdictions should make any Anglican happy, be he cessationist or continuationist.