Evening Prayer at St. Mary's

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Thursday, May 23, 2013 at 09:44PM

Thursday, May 23, 2013 at 09:44PM First, an update. While my readers are well aware that I have made my way out of the Anglican Catholic Church, I haven't mentioned where we ended up. Turns out that there was a little traditional Realignment parish of in our neck kof the woods I didn't know about until fairly recently. Well, long story short, we visited and immediately fell in love the with people there. The service is MOTR, and there are only a couple of "contemporary" flourishes thrown in (e.g., "Our God Is An Awesome God"). But for the most part it is a basic Anglican liturgy.

I don't know at this point if we'll return to the Continuum or stay in the Realignment. Praying for God's guidance on this. I consider myself more of a classical Anglican Continuer than anything else, but perhaps God is showing me something new. I take it a day at a time.

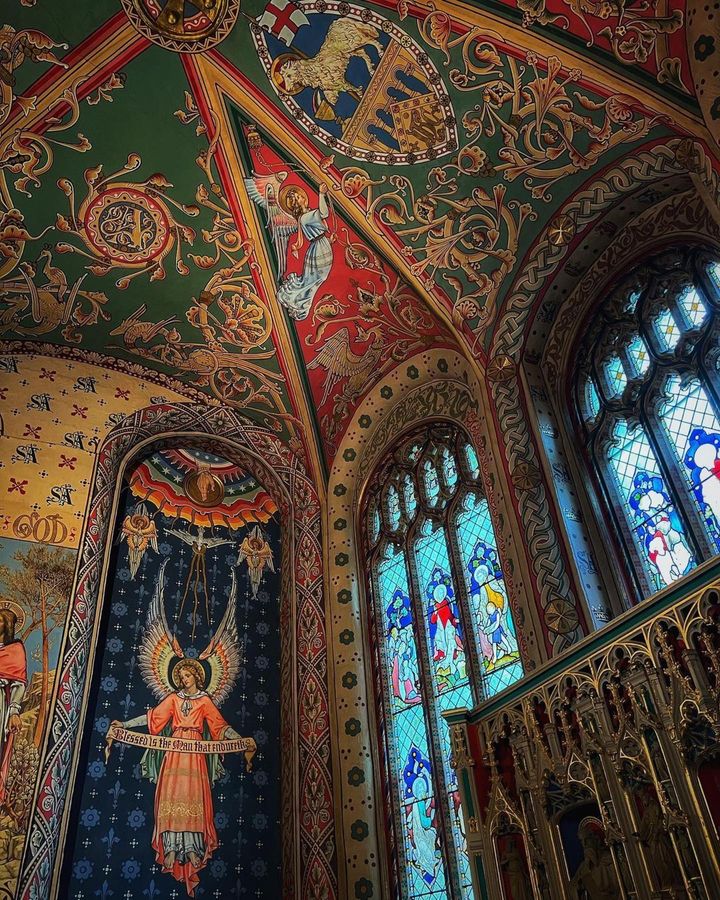

But last night I went back to Evening Prayer at St. Mary's. I did so because I had come to miss it, and the two gentlemen with whom I pray, one a postulant and the other an aspirant, missed me. It was good to see them again, and to pray there with them in St. Mary's beautiful little sanctuary:

I intend to pray Evening Prayer on Wednesdays as often as I can. For some reason, I can't give this up.

And it got me to thinking last night. When Kevin, Matt and I were there praying, we weren't two Anglo-Catholics and one Ango-Protestant. We were simply three brothers in Christ, praying the matchless prose of Cranmer's prayerbook. But it wasn't that prose which united us. It was simply the flame of prayer. The flame of the Holy Spirit.

I wondered last night if maybe Anglican unity, if it is to be achieved, will happen not because of the ecclesial machinations of bishops and other "movers and shakers", but because we all start recognizing Christ in the other. If lay people can reach across "party" boundaries to find fellowship with the other -- something not unknown in Anglican history -- maybe the bishops and the "movers and shakers" will follow.

David Virtue Interviews Susan Howatch (Touchstone)

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Tuesday, May 21, 2013 at 08:48PM

Tuesday, May 21, 2013 at 08:48PM I find Howatch to be a very interesting Anglican thinker, though I'm pretty sure I don't track with her 100%. Her novels on the Church of England and Anglican parties/churchmanships are not to be missed.

Anti-Calvinists: The Rise of English Arminianism c.1590-1640

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Saturday, May 18, 2013 at 01:11AM

Saturday, May 18, 2013 at 01:11AM I read this book, Nicholas Tyacke's doctoral dissertation published by Oxford University Press, some months ago. Tyacke presents an interesting thesis. Tonight I found a chapter-by-chapter summary of the book, which I post here for those who might be interested in reading it:

Abstract

This is a study of the rise of English Arminianism and the growing religious division in the Church of England during the decades before the Civil War of the 1640s. The widely accepted view has been that the rise of Puritanism was a major cause of the war; this book argues that it was Arminianism — suspect not only because it sought the overthrow of Calvinism but also because it was embraced by, and imposed by, an increasingly absolutist Charles I — which heightened the religious and political tensions of the period. Almost all English Protestants were members of the established Church. Consequently, what was a theological dispute about rival views of the Christian faith assumed wider significance as a struggle for control of that Church. When Arminianism triumphed, Puritan opposition to the established Church was rekindled. Politically, Charles and his advisers also feared the consequences of Calvinist predestinarian teaching as being incompatible with ‘civil government in the commonwealth’.

Introduction

This chapter introduces an story of the rise of English Arminianism and the growing religious division in the Church of England during the few decades which preceeded the Civil War in the 1640s. This view, which is widely accepted, has been that the rise of Puritanism was a significant cause of the war; this book argues that it was Arminianism — under suspicion partly because it sought the overthrow of Calvinism and also because it was acccepted by, and imposed by, an ever increasing absolutist Charles I — which heightened the religious and political tensions of the period. Almost all English Protestants were members of the established Church. As a result, what was a theological dispute about rival views of the Christian faith assumed greater significance as a struggle for control of that Church. When Arminianism succeeded, Puritan opposition to the established Church was reignited. Politically, Charles and his advisers also feared the consequences of Calvinist predestinarian teaching as being incompatible with ‘civil government in the commonwealth’.

1 The Hampton Court Conference and Arminianism avant la lettre

The Hampton Court conference was held in 1604 to discuss the status of the English Church and Arminianism along with a discussion on doctrine of predestination. At this conference Calvinism was discussed for the first time and it was also the last time when the predestinarian question was handled by the English religious leaders under the influences of the continental Arminian. The English hierarchy and the Puritans were the two authorized parties expected to discuss the state of the English Church at the conference after Puritan reformers failed to obtain new religious settlement from James. At the conference the Puritan stated that the Lambeth Articles needed to be added to the existing English confession of faith — the Thirty-nine Articles.

2 Cambridge University and Arminianism

In the early 1590s English Calvinism was very much in ascendant and much obvious at Cambridge University. At Cambridge a direct confrontation between Calvinism and anti-Calvinist sentiment erupted in 1595 during a university sermon delivered by William Barrett. Barrett decided to protest against a public lecture delivered by William Whitaker, Regius Professor of Divinity, ‘against the advocates of universal grace’, as his reply against the Cambridge Calvinists. As expected Barrett was asked to appear at the Cambridge Consistory Court and forced to recant, but Barrett then appealed to the Archbishop Whitgift. Some modern historians also have raised question against the Calvinism of the Lambeth Articles.

3 Oxford University and Arminianism

Cambridge and Oxford University followed Calvinism, but during 1590 there was a huge clash between Calvinism orthodoxy and emergent Arminianism at Oxford. The difference between these was explained on the basis of fact that anti-Calvinism was checked at Oxford around ten years previously. This differences were explained by Anthony Corro, who was an ex monk from San Isidro near Seville and taught at Oxford from 1579 to 1586. Corro published ‘Tableau de l'awre de dieu’ in 1569 and expressed his views on the three heads of the religion, namely: predestination, free will, and justification by faith alone. Corro also applied for and was refused an Oxford doctorate of divinity.

4 The British delegation to the Synod of Dort

The official British delegation at the Synod of Dort played a critical role in the rise of English Arminianism. This was an international Calvinist gathering, which condemned the doctrines of the Dutch Arminians in 1619 and catalysed the English religious thought in the early 17th century. Soon news of the Arminian controversy spread to Holland, at the Synod of Dort, and the controversy was discussed far and wide. As a result of this gathering, differences among English theologians were brought out in the open. After this gathering, suspension of judgement on the nature of the relationship between grace and free will became harder, and scholars directed their studies to resolve this problems.

5 Bishop Neile and the Durham House group

During the 1620s there was a transformation in the official Church of England teachings. Bishop Neile became an important element in the religious transition during this decade by establishing the system of Arminian patronage and protection. The role of John Hacket contrasted with role of Neile in terms of his theological seniors, which pleased all sides by their touching opinions about predestination and converting grace; they made no discrimination about which or which propugners should be gratified in their advancements. He went through more bishoprics than any of his contemporaries such as Rochester, Coventry, and Lichfield, Lincoln, Durham, Winchester, and York.

6 Richard Montagu, the House of Commons, and Arminianism

The debates over Calvinism and the Lambeth Articles were provoked by the anti-Calvinist writings of Richard Montagu in the 1620s. His opponents tried to link his writings and books with a conspiracy to topple the established teachings of the English Church. The parliamentary case against Montagu involved his two works published in 1624 and 1625 titled ‘A new gagg for an old goose’ and ‘Appello Caesarem’. Montagu also countered both local missionary activities and the latest Catholic apologetic. He also tried to defend himself from attacks by fellow Protestants who considered his writings to be against Arminian teachings.

7 The York House Conference

The House of Commons failed to prosecute Richard Montagu before the House of Lords. In 1624, the Commons referred the Montagu case to the Archbishop Abbot and forwarded a complaint against Bishop Harsnett of Norwich to the House of Lords. A conference was held in February 1626 under the chairmanship of Buckingham and the second session of this conference was attended by Montagu, at Buckingham's residence, York House in the Strand. The subject of this conference was the published view of Montagu and according to Buckingham the conference had been arranged at the request of the Earl of Warwick. The York House conference was designed to defeat the prosecution of Montagu by the House of Commons.

8 Arminianism during the Personal Rule and after

The rise of anti-Calvinist sentiment became considerable in terms of both power and number. During the reign of Charles, the King decided to go against those who claimed to be on God's side, by favouring a clerical group prepared to preach monarchical authority in defence of its beliefs. Laud and Neile now actively sought to enforce Charles's religious declaration of 1628 throughout the dioceses of England and Wales, which meant in effect the proscription of Calvinism. Having the royal support Laud and Neile were now free to implement their ideas. The consequences of the rise of Arminianism were serious for the contemporary Puritanism, as it altered the doctrinal basis of English Church membership.

Conclusion

Along with various other issues, religion played a major contributory role in the English Civil War. The religious fears voiced in the late 1620s were given increasing substance during the 1630s. The term Arminian is the least misleading among the terms which can be used to describe the religious change of this time. The term Arminian denotes a coherent body of anti-Calvinist religious thought, which was gaining ground in various regions of early 17th-century Europe. Calvinism was also attacked as being unreasonable. The rise of English Arminianism challenged the Calvinist world picture, which envisaged the forces of good and evil involved in a struggle that would only end with the final overthrow of the Antichrist.

Gaelic Psalms at Back Free Church, Isle of Lewis

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Saturday, May 18, 2013 at 12:01AM

Saturday, May 18, 2013 at 12:01AM Otherworldly.

TEC's PBess Claims Paul Was Wrong to Cast Out Slave Girl's Demon

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Thursday, May 16, 2013 at 10:35AM

Thursday, May 16, 2013 at 10:35AM Presiding bishop preaches in Curaçao, Diocese of Venezuela

Human beings have a long history of discounting and devaluing difference, finding it offensive or even evil. That kind of blindness is what leads to oppression, slavery, and often, war. Yet there remains a holier impulse in human life toward freedom, dignity, and the full flourishing of those who have been kept apart or on the margins of human communities. It’s a tendency that seems to emerge along a common timeline. Formal legal structures that permitted human slavery ended here and in many parts of the world within a relatively short span of time. It doesn’t mean that slavery is finished today, but at least it’s no longer legal in most places. Even so, slavery continues in the form of human trafficking and the kind of exploitation that killed so many garment workers in Bangladesh recently.

We live with the continuing tension between holier impulses that encourage us to see the image of God in all human beings and the reality that some of us choose not to see that glimpse of the divine, and instead use other people as means to an end. We’re seeing something similar right now in the changing attitudes and laws about same-sex relationships, as many people come to recognize that different is not the same thing as wrong. For many people, it can be difficult to see God at work in the world around us, particularly if God is doing something unexpected.

There are some remarkable examples of that kind of blindness in the readings we heard this morning, and slavery is wrapped up in a lot of it. Paul is annoyed at the slave girl who keeps pursuing him, telling the world that he and his companions are slaves of God. She is quite right. She’s telling the same truth Paul and others claim for themselves.[1] But Paul is annoyed, perhaps for being put in his place, and he responds by depriving her of her gift of spiritual awareness. Paul can’t abide something he won’t see as beautiful or holy, so he tries to destroy it. It gets him thrown in prison. That’s pretty much where he’s put himself by his own refusal to recognize that she, too, shares in God’s nature, just as much as he does – maybe more so! The amazing thing is that during that long night in jail he remembers that he might find God there – so he and his cellmates spend the night praying and singing hymns.

No further comment necessary.

The Conciliar Anglican (Fr. Jonathan) on The Rise of Parties

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Sunday, May 5, 2013 at 09:03PM

Sunday, May 5, 2013 at 09:03PM Update 5/14: Having carefully read Fr. Chadwick's two posts (three if you count this one) on yours truly, the Embryo Parson, I have concluded there's really no point in posting a detailed response after all. This for three reasons: 1) the essence of Fr. Chadwick's assessment is that I am a) a "fanatic"; and b) a "Calvinist" with latent iconoclastic tendencies. Interestingly, he admits he's never read Calvin, and in this very illuminating post he is taken to task by a couple of his own followers, including William Tighe, over the historical inaccuracies and errant judgments he sets forth in the post regarding the Reformer. It would appear, contrary to his assertion, that he's not read this blog either, otherwise he'd have concluded that I call myself an Augustinian, not a Calvinist, and that I'm the furthest thing from an iconoclast. Chadwick's response amounts to nothing more than name-calling, and name-calling is not an argument. It is impossible to rebut a non-argument, other than to identify it as such. So, I'll simply leave it to objective readers to peruse this blog and determine for themselves if Fr. Chadwick's assessment is anywhere close to being accurate; 2) a detailed response, however invigorating it might be to write it, would only serve to generate more heat than light. I am more concerned about shedding light on Anglo-Catholic revisionism for the interested than I am in heated pissing contents with the uninterested; 3) at the end of the day, all I really care about is living the Gospel according to the Anglican Way. More often than not that will mean avoiding strife with other Christians when it is possible to do so. It is not always possible to do so, of course, but it is possible in this particular instance.

Update 5/6: I see tonight that Fr. Chadwick has commented on this post. I will address his comments when I have a big enough block of time to do so in depth.

____________________________________________________

Fight For Your Right to Parties

A salient part of the article:

Anglo-Catholicism and Evangelicalism both began as reform movements aimed at bringing Anglicans back to their roots. This is easily forgotten today, as both movements have become more concerned with aping their corollaries in the wider Christian world than with celebrating Anglican distinctiveness. Nevertheless, the early Evangelical movement in Anglicanism was deeply concerned with communicating the Gospel by means of both impassioned preaching and liturgy. The great Evangelical Charles Simeon wrote gushingly of his love for the prayer book and his belief that “a congregation uniting fervently in the prayers of our Liturgy would afford as complete a picture of heaven as ever yet was beheld on earth.” He distrusted Evangelical efforts that were not grounded in the prayer book. He also joined his fellow Evangelical John Wesley in having a special devotion to Holy Communion, something that had fallen out of fashion in the latter half of the eighteenth century.

In the beginning, the Anglo-Catholic movement was equally imbued with the spirit of the Elizabethan Settlement. There is a fierce desire apparent in the early Tracts for the Times to associate the Church of England not only with its pre-Reformation past but also with the great lights of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Much of what is available from the reformers and divines today was re-published and circulated by early Anglo-Catholics, from the commentaries and sermons of William Beveridge to Richard Hooker’s Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity. Moreover, the early movement was deeply concerned with maintaining the prayer book as the standard for doctrine and faith. Early Anglo-Catholics objected to schemes that would allow for non-subscription to the 39 Articles by those obtaining university posts. Even Tract 90, which was admittedly an effort to find ways around uncomfortable parts of the Articles, was nevertheless an indication of how committed the Oxford Fathers were to explicating the Catholic character that they believed Anglicanism has always had.

The point is, both Evangelicalism and Anglo-Catholicism can legitimately claim a stream of continuity with classical Anglicanism. Moreover, both parties, as reform movements, are able and fitted to make sure that modern Anglicans do not lose an important part of our theological heritage. Evangelicals are well poised to remind us of the ultimate authority of Scripture within the Church, the all sufficiency of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, and the need for personal conversion. Anglo-Catholics, on the other hand, remind us of the power and importance of the Sacraments, the nature of the Church as a divine institution, and the guiding principle of Anglicanism that we judge all of our doctrine and practice by how it relates to the early Church. A full and true Anglicanism has to have all of these things to function.

Amen and amen to that. As Fr. Jonathan goes on to point out, however, there is a worsening divide in Continuing Anglicanism between Evangelicals and Anglo-Catholics, and unless we find a way to heal this divide the prospect of Continuum unity looks bleak. His prescription therefore:

What has been missing from (the effort to find common ground), however, has been a genuine commitment from all sides that the basics of classical Anglicanism are where that common ground is to be found, not in appeal to the lowest common denominator of what we are able to say together currently. In practice, what that means is that we have to be prepared to be challenged by one another by means of the very same formularies. Evangelicals do not need to run out and start buying incense, but they ought to be able to receive the Anglo-Catholic emphasis on the sacraments and the orders of ministry not as quirky things that those people do but as a genuine expression of what Anglicans have believed since long before there was such a thing as Church parties. Equally, Anglo-Catholics must concede that the formularies are clear about things like the authority of Scripture and justification by faith, and they must genuinely find a way to make peace with our Reformation heritage.

The problem is, I see much more of a willingness on the part of Evangelicals to embrace an "emphasis on the sacraments and the orders of ministry" than I do anything even approaching a concession from *modern* Anglo-Catholics "that the formularies are clear about things like the authority of Scripture and justification by faith, and they must genuinely find a way to make peace with our Reformation heritage". Quite the opposite is true. See for example this blog entry from Fr. Anthony Chadwick, where he raises the old "Calvinism" bugaboo and where the ACC's metropolitan Mark Haverland chimes in saying, "Father Hart is much more enamored of the Articles and Tudor divines than I. . . ." One need only peruse the blog articles and comments of modern Anglo-Catholic clerics such as Chadwick and Haverland or witness the massive theological rewrite that is the ACC's new web page to see where modern Anglo-Catholics (who as Fr. Jonathan notes have jettisoned the comprehension ideal seen even in the Tractarians) are going. Of this phenomenon, Bishop H. Lee Poteet writes:

The problem for the ACC at the moment is that too many of their clergy and not a few of their laity appear more to be playing Church than being The Church. The priest who said “We have the Church WE want” forgot to question if it was the Church which God wanted.

Bingo. And if these modern Anglo-Catholic sectarians get their way by getting the church THEY want, well as I wrote over at the Anglican Diaspora this afternoon in response to Fr. Richard Sutter:

My prediction is that any "one Anglo-Catholic body" that manages to cobble together some sort of "pure church" consisting of carve-outs from the various Anglo-Catholic expressions within the Continuum is bound to die out eventually, probably sooner rather than later. Not only will it continue to bleed people to both Rome and Orthodoxy, as it has been doing ever since it appeared back in 19th century, but it will languish, stuck in mere aestheticsm with no sense of apostolic purpose. Meanwhile, Anglicans who understand and embrace the Gospel of Jesus Christ, whether from the Continuum or those awful "generic low-church and charismanic sects" such as the ACNA and other bodies of the Realignment, will enjoy the blessing of God and accordingly see growth. There are signs even now that these classical Anglican folks in the Continuum and the Realignment are coming together for the cause not only of Anglican unity but for the cause of bringing the Gospel to a lost world.

So, it remains to be seen whether or not Anglo-Catholics in the Continuum will be able to participate meaningfully in the kind of classical Anglican comprehensiveness to which Fr. Jonathan and others call us. As I've said before, so much the worse for them if they can't.

A Blessed Rogation Sunday to All

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Saturday, May 4, 2013 at 11:45PM

Saturday, May 4, 2013 at 11:45PM Some more (very lovely) William Byrd for you tonight:

Wanted: An Adult Faith in a Youth Culture

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Friday, April 26, 2013 at 12:02AM

Friday, April 26, 2013 at 12:02AM Here's a related one from The Moody (!) Standard: Students and professor discuss liturgical churches and worship. As I noted in the combox, however:

A good article, though I would take issue with Liftin’s statement:

“If you plopped an ancient Christian down in modern times and eliminated the language barrier, he would most easily recognize the Eastern Orthodox service. If he entered a contemporary Evangelical church he’d probably think he had visited a service of Gnostic heretics.”

I seriously doubt that a second-century Christian would “easily recognize” the Eastern Orthodox Divine Liturgy. The Orthodox liturgy has centuries of liturgical accretions that the Christian from the 2nd century would find not only odd, but likely off-putting and even inappropriate. On the other side of it, the 2nd century Christian would likely recognize the reading of Scripture, the preaching and the prayers of the Evangelical service, though he would wonder where the weekly Eucharist is and why all those damned electric instruments are blaring. If the account of the liturgy from St. Justin Martyr is any indication, I’d say the 2nd-century Christian would be most at home in a modern Anglican low church service.

Why Traditional Churches Should Stick with Traditional Worship

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Friday, April 19, 2013 at 12:09AM

Friday, April 19, 2013 at 12:09AM It’s an article of faith these days that contemporary worship is the way to go if you want your church to grow. Thousands of churches will be planted this year – and every one will offer contemporary worship. Hymns are out – love songs to Jesus are in.

Traditional churches have seen young believers flocking to megachurches, so naturally they want to get in on the growth. But this is foolish. Traditional churches lack the musical depth, computer controlled lighting and sound equipment that are needed to generate the “praise-gasm” that young believers associate with God. Rock music seems out of place in a brightly lit chapel a communion table and stained glass.

People come to church to encounter God. A good worship service is transcendent; it helps people detach from this present world to connect with the divine. But when traditional churches try to be contemporary it usually comes across as forced, stilted or artificial. This dissonance jerks people back into the mundane world. Worshippers focus on the distraction instead of the Lord.

A Checklist for Finding a Classically Anglican Parish

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Thursday, April 18, 2013 at 09:40AM

Thursday, April 18, 2013 at 09:40AM From The Conciliar Anglican. Not that we should be purists. If it's Anglican and traditional, generally speaking it will be good, and therefore a place where we can be fed and serve wholeheartedly. But inasmuch as some Anglicans question the "Classical Anglican" designation, I link this blog entry with a view toward explaining what classical Anglicanism is.

Psalm 8, Chanted

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Monday, April 8, 2013 at 01:47AM

Monday, April 8, 2013 at 01:47AM Play this mp3 file, and as you listen, read the following from the Psalter of the 1662 BCP:

Domine, Dominus noster

Psalm 8. O LORD our Governor, how excellent is thy Name in all the world : thou that hast set thy glory above the heavens!

2. Out of the mouth of very babes and sucklings hast thou ordained strength, because of thine enemies : that thou mightest still the enemy and the avenger.

3. (When I ) consider thy heavens, even the works of thy fingers : the moon and the stars, which thou hast ordained.

4. What is man, that thou art mindful of him : and the son of man, that thou visitest him?

5. Thou madest him lower than the angels : to crown him with glory and worship.

6. Thou makest him to have dominion of the works of thy hands : and thou hast put all things in subjection under his feet;

7. All sheep and oxen : yea, and the beasts of the field;

8. The fowls of the air, and the fishes of the sea : and whatsoever walketh through the paths of the seas.

9. O Lord our Governor : how excellent is thy Name in all the world!

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son : and to the Holy Ghost; As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be : world without end. Amen.

Psalm 150 - Sunday Choral Evenson

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Monday, April 1, 2013 at 10:03PM

Monday, April 1, 2013 at 10:03PM Now THAT's a procession. But as discussed with Mr. Veitch over at the UECNA Facebook page tonight, when we have remarried this worship to Settlement theology, we'll be back where we should be.

A Day Late, But a Joyful Eastertide to All!

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Monday, April 1, 2013 at 09:53PM

Monday, April 1, 2013 at 09:53PM This joyful Easter-tide,

Away with sin and sorrow!

My Love, the Crucified,

Hath sprung to life this morrow.

Refrain

Had Christ, that once was slain,

Ne’er burst His three day prison,

Our faith had been in vain;

But now hath Christ arisen,

Arisen, arisen, arisen!

My flesh in hope shall rest,

And for a season slumber;

Til trump from east to west,

Shall wake the dead in number.

Refrain

Death’s flood hath lost its chill,

Since Jesus crossed the river:

Lover of souls, from ill

My passing soul deliver.

Refrain

Palm Sunday!

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Sunday, March 24, 2013 at 01:54AM

Sunday, March 24, 2013 at 01:54AM A blessed Holy Week to all! Fr. Hart's sermon.

1 Ride on! ride on in majesty!

Hark! all the tribes Hosanna cry;

O Saviour meek, pursue Thy road

With palms and scatter'd garments strow'd.

2 Ride on! ride on in majesty!

In lowly pomp ride on to die:

O Christ, Thy triumphs now begin

O'er captive death and conquer'd sin.

3 Ride on! ride on in majesty!

The wingèd armies of the sky

Look down with sad and wondering eyes

To see the approaching sacrifice.

4 Ride on! ride on in majesty!

Thy last and fiercest strive is nigh;

The Father on His sapphire throne

Awaits His own anointed Son.

5 Ride on! ride on in majesty!

In lowly pomp ride on to die;

Bow Thy meek head to mortal pain,

Then take, O God, Thy power and reign.

Peter Toon on the 1979 Prayerbook

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Sunday, March 3, 2013 at 09:59PM

Sunday, March 3, 2013 at 09:59PM Happily, the Neo-Anglicans seem to be rethinking usage of the 1979 prayerbook, pondering whether or not a modern version of the 1662 BCP might be in order.