Collect for the 10th Sunday of Trinity

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Thursday, August 25, 2022 at 09:58PM

Thursday, August 25, 2022 at 09:58PM The Collect for the 10th Sunday after Trinity from the Book of Common Prayer (BCP), set to the beautiful music of Thomas Mudd.

For those not acquainted with Anglicanism, a "Collect" is a short prayer that appears in our liturgy and daily offices (Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer). Last Sunday was the 10th Sunday after the feast of the Holy Trinity, and we prayed this prayer near the beginning of last Sunday's Holy Communion service and it will continue to be prayed in our Morning and Evening Prayers from the BCP this week.

"LET thy merciful ears, O Lord, be open unto the prayers of thy humble servants; and, that they may obtain their petitions, make them to ask such things as shall please thee; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen."

What's Up With Fr. Robert Hart?

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Wednesday, August 24, 2022 at 09:30PM

Wednesday, August 24, 2022 at 09:30PM I'm not sure what has happened to him, but it seems to be in concert with the spiritual fall of his two brothers, David Bentley Hart and Addison Hodges Hart, who seem to have departed from orthodox Christianity for some sort of perennialism. Robert, while apparently still orthodox and a priest canonically resident in the Anglican Catholic Church, is going into some dark, angry place. He seemed to be a mostly kind, reasonable and scholarly fellow when I first met him online back around 2008. His older articles at the blog The Continuum are still today very valuable to those who are seeking to learn about Continuing Anglicanism, but something seems to have happened to his spirit a few years ago, and these screenshots are indicia. Nowadays, in my experience anyway, he just snarls at his critics and rarely if ever engages them rationally. I know several priests who have blocked him on Facebook. I had to remove him from my own Facebook discussion group on Continuing Anglicanism. Today I deleted the link to The Continuum blog from my sidebar and a few other references to him in my blog articles. (It's not because The Continuum isn't an excellent Anglican blog. It is. It's just that I no longer want to send people his way.)

Where is his Ordinary in all this?

As these recent screenshots from his Facebook page indicate, he apparently has a severe case of Trump Derangement Syndome (TDS), hates Republican voters and has absolutely no sense of priestly bearing.

Are all his parishioners Democrats? Are they all TDSers like him? That's hard to imagine since the Anglican Catholic Church and other Continuing Anglican jurisdictions tend to be very politically conservative. Since I live in North Carolina I just might pay a visit to his parish St. Benedicts in Chapel Hill one day to observe, hoping he doesn't throw me out as a "Trumpublican piece of $#!+".

Let us pray he snaps out of it. Seriously.

P.S.: If anyone of you out there thinks that Christians who are critical of Anthony Fauci are guilty of bearing false witness, read RFK Jr. on the matter. This is the definitive work on Fauci's corruption. He is not a good man, and the fact that Fr. Hart thinks otherwise is illustrative of his overall political delusion.

Requiem for David Bentley Hart

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Sunday, August 14, 2022 at 07:37PM

Sunday, August 14, 2022 at 07:37PM First Things recently posted these two articles by The Rev. Dr. Gerald McDermott, a traditional Anglican priest and scholar, on the downward trajectory of David Bentley Hart:

I urge you two read both articles, including DBH's response linked in the second one, which only illustrates McDermott's point about DBH's penchant for vituperation in response to his critics. DBH is a great mind; just ask him. But he's a nasty soul. (Seems to run in the family.)

More unfortunately, it appears he's run off the rails, abandoning Orthodoxy for perennialism. Keep an eye on his future to see just where he ends up. I hope it is back in Orthodoxy, I mean true Orthodoxy, but I am not optimistic.

Man Up

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Sunday, August 14, 2022 at 12:03AM

Sunday, August 14, 2022 at 12:03AM "What he essentially says is: man up!"

And buy and learn to use an AR-15.

David Virtue's Irrational Hoplophobia - Postscript

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Friday, August 12, 2022 at 08:23PM

Friday, August 12, 2022 at 08:23PM I don't know whether I should expect a response from David Virtue to this series of rebuttals. He has banned me from his Facebook page and has apparently prohibited me from commenting at the Virtue Online web site and his Facebook page dedicated thereto, but I won't respond in kind. I will keep the comments section here open for him should he muster the resolve to reply. That goes as well for anyone who takes his side on this issue. If he chooses to reply publicly elsewhere, I will copy and post that reply here for dissection.

For those of you who may be wondering why an Anglican priest is so adamant about this hot button political issue, I will repeat what I said here:

All liberals and some conservatives (religious and political) will write me off when I say that American gun control activism is of the Evil One. I don't give a tinker's damn about their opinions. I really do believe that my former and present gun-rights activism constitutes a war against the devil. That's my story and I am sticking to it. Hear me out.

First, for the devil to achieve his goals against traditional Christian culture, he is going to have to wage an intense war against those parts of the former Christendom that harbor gun cultures. He has been largely successful throughout the Commonwealth due to its benighted Hobbesian deference to government. The citizens of the UK, Canada, Austrialia, New Zealand et al. have essentially surrendered their arms to the state. And that having been done, just look at how that those states are now coming against the traditional rights of Englishmen and the Church. Our American Founding Fathers knew this could happen, they warned us about it, and they therefore set some things into fundamental American law, arguably the most important of which is the right to keep and bear arms.

Second, in John 8:44 Jesus said that Satan "was a murderer from the beginning." And so he takes GREAT delight in advancing his war against traditional Western culture, liberty and the Church by sending crazed gunmen to slaughter children. He gets two for the price of one.

I am convinced that I am accurately assessing this thing. Change my mind.

And that being what it is, I excoriate conservative Christians who are in a dalliance with liberal hoplophobes, including a few trad Anglicans I know. For some inscrutable reason they find themselves hauling water for religious leftists. I find it just absolutely astounding.

So I will just come out and say it right here with reference to C.S. Lewis' "The Last Battle": if you support banning weapons like the AR-15, you serve Tash (though you might get let off the hook if you're Puzzle).

You need to understand that I absolutely believe disarmament laws of the type Virtue supports *are of the devil*. That is a belief based not only on historical observation, but yes, even on biblical principles and the mind of the Church with respect to the issues of self-defense and just wars. I welcome all comers who demur, provided they do so with a commitment to facts and logic.

ΜΟΛΩΝ ΛΑΒΕ

Communitarians, Neorepublicans and Guns: Assessing the Case for Firearms Prohibition, David B. Kopel and Christopher C. Little, Maryland Law Review, Volume 56, Issue 2 (1997)

David Virtue's Irrational Hoplophobia - Part 6 in a Series

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Wednesday, August 10, 2022 at 06:10PM

Wednesday, August 10, 2022 at 06:10PM This is the latest tirade from David Virtue in his quixotic campaign to move the United States to enact the kind of draconian gun control legislation other countries have. Here he rhetorically turns his back on us "AHOLE Americans" and addresses his friends in the countries mentioned in a condescending attempt to explain us to them. Again, I respond in italicized bold:

"TO ALL MY FRIENDS IN ENGLAND, EUROPE, CANADA, AUSTRALIA, NEW ZEALAND, SOUTH AMERICA AND AFRICA. . . .

You write and ask me why is there such an obsession with guns in this country.

Many who die are suicides which, if there were not the easy availability of guns most would still be alive today. I knew two fathers who lost sons to suicide because loaded hand guns were in the home. In 2021 that figure was 24,000 and rising, about 70% of all deaths. The total number of killings topped 45,222 in 2021. At the present murder rate, it could easily reach 50,000 by the end of 2022. That’s the equivalent of the city of Nelson, NZ or Horsham, England."

I wonder how "Dr." Virtue reaches the conclusion that most deaths by suicide wouldn't have happened had it not been for the easy availability of guns. I'm calling on him here to publicly explain that.

I also wonder why Virtue, in accordance with logical consistency, doesn't address the easy availability of alcohol, which "causes" three times as many deaths annually as the easy availability of guns do. I'm calling on him here to publicly explain that one as well.

As to why guns are easily available, well, I have addressed in previous parts of this series, but Virtue sums it up in the next sentence:

Guns are held in the name of freedom and something called the Second Amendment.

Yes, "something" called the Second Amendment.

"The 2nd amendment was written at a time of single shot flintlock rifles. The 2nd amendment never envisaged the general populace buying or owning an AR-15 or AK 47."

I have addressed this silly argument in Part 3.

It never envisaged an 18-year-old who is too young to buy liquor walking into a gun store and buying a loaded semi-automatic AR-15 and then walk into a school and slaughter children.

I wonder how Virtue knows what the Founding Fathers envisaged. Perhaps he should public explain this one too. As I've already demonstrated, the Founding Fathers were learned and intelligent Englightenment men who were aware of all manner of developing technologies, some of them involved in that development (Benjamin Franklin and electricity). As to firearms, they knew of the Puckle Gun and the Giradoni Rifle, both prototypes of automatic fire weapons. They knew what primitive firearms technology was, how it was evolving, and where it was likely to go, and I maintain that if they were alive today they'd be on the side of us "gun nuts." Their political philosophy would demand it. The likely knew that evolving technologies would in many cases mean increased dangers, but they would accept those potential dangers, especially when rights are involved, in accordance with a cost-benefit analysis. In other words, they knew that liberty could be dangerous, but they chose liberty over security instead.

Today, these slaughters are the Republicans’ human sacrifices to the 2nd amendment. The most recent killing in Illinois, a 21-year-old white male bought not one but five weapons, two were semi-automatic AR-15s.

"These slaughters are the Republicans’ human sacrifices to the 2nd amendment." Here again, as is his wont, Mr. Virtue resorts to angry invective and inflammatory language, which while not technically libelous, is libelous in spirit. It is a form of false witness.

We are repeatedly told that guns don’t kill people, people kill people, probably the stupidest one liner in the history of one liners. The killers are both black and white. Black on black killings predominate in cities; in the broader populace killings it is white and people of different ethnic groups. Another fiction is that there are more deaths in Democratic states than Republican. A person wanting to go on a killing spree in Illinois can buy a gun in Indiana and cross state lines with nobody checking.

Yet in all that dog of a comment he never explains why the slogan is stupid. Is it not the case that metallic manufactured items don't do things unless used or set in motion by people? What a strange metaphysical notion to argue otherwise. In his 11th Homily on Romans, St. John Chrysostom uses weaponry as an analogy with respect to the role of the flesh in spiritual warfare:

"'Neither yield ye your members as instruments of unrighteousness unto sin...but as instruments of righteousness.'

The body then is indifferent between vice and virtue, as also instruments (or arms) are. But either effect is wrought by him that uses it. As if a soldier fighting in his country's behalf, and a robber who was arming against the inhabitants, had the same weapons for defense. For the fault is not laid to the suit of armor, but to those that use it to an ill end."

So, the argument that guns don't kill people but people kill people is not so stupid at all. It is true on its face, and even The Goldenmouth would apparently agree.

The US Supreme Court recently upped the ante allowing concealed carry laws in some states thus allowing men and women to carry guns which, on an impulse, or an argument over a parking space one or both parties can pull out their hidden hand weapon and shoot. The gun has now replaced the middle finger. You have been warned. The United States leads the world in total number of people incarcerated, with more than 2 million prisoners nationwide.

And here we are treated to yet another of Virtue's hysterical assessments. Perhaps it has escaped his notice that 38 states have legalized concealed carry, yet shootings involving licensed carriers over parking spaces and suchlike almost never occur. Back in the day when we gun-rights activists were fighting for concealed carry, the hoplophobe left predicted mayhem on the streets.

It didn't happen. We proved them wrong, and David Virtue is wrong with them.

Apparently, Jesus wants Americans to be armed to the hilt to kill nonexistent communists living in Boise, Idaho but willing and able to kill their neighbors because any moron can buy and own a gun. Many of the killers write manifestos declaring their intention and nobody challenges them because of free speech issues. Threats abound to people who oppose the NRA an organization so corrupt it is under investigation by the attorney general of New York State in connection with its lawsuit that seeks to dissolve the NRA for an alleged pattern of self-dealing.

And there he goes again with his emotive rhetorical overreach. We gun owners believe "Jesus want's Americans. . . etc., ad nauseam." Yet another unchristian caricature of American gun owners.

As for the NRA, while some reforms are needed, our organization will survive. Even one of its critics says so:

But while it may be tempting to cheer the organization’s troubles, the NRA isn’t dead yet. “It will reconstitute itself without a problem,” an anonymous former Trump adviser told Politico on Friday. The NRA isn’t the only gun-rights organization in the U.S., either; the Politico piece even mentions a few, like Save the Second and Gun Owners of America, and some view the NRA as being unacceptably moderate. Even if the NRA did shut its doors, it seems entirely likely that some other group will attract the group’s donors. As long as the money flows — and it will — gun-rights lobbyists will find jobs.

This past weekend on July 4. . . . (long, meandering rant snipped here in the interest of brevity. You can read it at his site. It's basically a litany of woes about gun violence.)

With all the guns already in existence there is no stopping the killings. None. Not only can teenagers buy semi-automatic weapons, rising illegal drug use with its own gun culture, and the easy purchase of guns, no one is safe anywhere any more in America. Red flag laws will be flouted. Gun laws in some states are as open as a colander, the massacres will continue, they will never stop.

Well then I guess there's no stopping the killings, because all the guns already in existence are not going to magically disappear, though Virtue may rant and rave and wish otherwise until he's blue in the face. Nor will the sale and purchase of millions of fireams be prevented in the future. That being the case, Virtue and his fellow hoplophobes in the the US, the Anglosphere, Europe and South America are going to have to find another narrative, you know, a narrative that is far more realistic, like praying for national spiritual renewal and hardening targets.

My wife and I never shop together any more in big box stores, only in open farmers markets where you can duck behind a tree if some NRA loving gun slinger pulls out his semi-automatic weapon and starts shooting.

Poor David and his wife, living in such abject, irrational fear of us "NRA loving gun slingers". But now that he's alerted us publicly, I'm going to tell all my fellow NRA members to start frequenting open farmers markets and look for the Virtues hiding behind a tree. ;)

Seriously, here once again Virtue resorts to an unchristian, vituperative attack on American gun owners, most if not the vast majority of whom are Christians of one form or another. Like I said, this is standard fare from him. If Virtue were not an Anglo-Protestant but rather an Anglo-Catholic, as a priest I would enjoin him to repent and go receive the sacrament of Confession. But he is an Anglo-Protestant, so as a priest I would counsel him to confess to God for his sinful acerbic rants which are devoid of any degee of Christian reason or charity.

The future of America is all downhill. Our politics are a mess, evangelicals are mostly vacuous, theologically empty-headed “Christian” nationalists who can’t figure out the difference between the Kingdom of God and the “Kingdom” of America, while a former president controls the Republican Party. Democracy is on the line. Civil War is a real possibility if people continue to promote and believe the Big Lie. And America has millions of guns to make it happen.

Three things:

1) We're treated once again to an instance of Virtue's unchristian inflammatory rhetoric, devoid of all reason, and what's more, it's an instance of the ad hominem fallacy;

2) It's also an instance of the hasty generalization fallacy. Virtue can't pretend to know the mind of Evangelicalism at large on the basis of his limited experience;

3) And I always laugh at modern Anglo-Protestants who rant and rave about "Christian Nationalism", when Anglo-Protestantism is the natural offspring of English Christian Nationalism (Erastianism). Virtue prays his Offices and observes the service of Holy Communion from a book that emerged from English Christian Nationalism.

But that is a topic for another day

FOOTNOTE: England, NZ and Australia all banned semi-automatic weapons after mass shootings. They have never had a repeat mass shooting.

FOOTNOTE: Causal fallacy, and once again, the US is not England, NZ, Australia, Canada or any other statist nation in the Anglosphere, Europe or South America. We are the United States of America, and in the United States of America the right to keep (possess) and bear (carry) arms is settled constitutional law. That means hundreds of millions guns including so-called "assault weapons" with their proper furnishings, and an untold number of stockpiled rounds of ammunition. No gun control laws patterned after the law of New Zealand and Australia will ever be enacted here. Get used to it, Dr. Virtue.

David Virtue's Irrational Hoplophobia - Part 5 in a Series

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Wednesday, August 10, 2022 at 05:59PM

Wednesday, August 10, 2022 at 05:59PM This article, "The Uvalde School Shooting is Complicated", was penned by Virtue Online contributor Mary Ann Mueller and published there in the aftermath of the Uvalde shooting. It is a long, rambling, emotional, mostly contentless piece, but I hope my readers will suffer through it for my replies in italicized bold.

"I see no need for civilians to be in possession of military-style assault rifle firearms such as the AK-47 or the AR-15, the Gatling gun or the machine gun. Those weapons are designed for warfare."

As I pointed out here, those who make such arguments are:

"either oblivious to or willfully suppresses the fact that *all* weapons are designed to kill human beings, or animals or both. That is what a "weapon" is. Moreover, not for Virtue, apparently, is the fact that the right to keep and bear arms as enshrined in the Second Amendment to the United States and as reaffirmed by the United States Supreme Court in the Heller, McDonald and recent Buren decisions protects exactly the kind of firearms he decries, mainly firearms suited for military use (e.g., the AR platform). The Second Amendment, which at the time of its drafting had neither recreational shooting or hunting in mind, but connection with the needs of a "well-regulated militia". This was affirmed in the 1939 US Supreme Court U.S. v. Miller.

At the time of the amendment's drafting and adoption, black powder rifles, handguns and other small arms were the weapons used by the militia and Continental Army. And the amendment says the "the people" have the right to own such arms. Gun-control advocates such as Virtue repeatedly trot out the trot out the tired, old argument that the Founding Fathers could not have foreseen the technological development of more potentially legal weaponry, but this false on its face. The Founders were learned men of the Enlightenment conversant with old and evolving technologies of all kinds, and they accordingly knew that military small arms technology would continue to evolve. Thomas Jefferson owned two Giradoni rifles, a precursor to automatic-fire technology. The Puckle Gun, patented in 1718, was an early Gatling Gun.

And with every new development of military small arms - muzzle-loading to breech loading, single shot to multiple shot (revolvers, lever action rifles and bolt-action rifles), to semiautomatics (late 19th century), to full automatics - American civilians were deemed to have just as much a right to access the evolving technology as the military did. This argument commonly spewed by hoplophobes that the Second Amendment does not guarantee the right to own "weapons of war" is therefore roundly defeated."

Furthermore, it is not for Virtue, Mueller, any other hoplophobe or some state or federal legislature to tell us gun owners what kinds of firearms we "don't need." As the saying goes, "It's a Bill of Rights, not a Bill of Needs". Military-style firearms with 30-round magazines are precisely the kind of firearm we might need in certain situations. Think community defense in the aftermath of a natural disaster. Think Kyle Rittenhouse.

"Right now, the Ukrainians would like to get their hands on as many military-style assault rifles as they can as they fend off Russian military aggression"

Which, in light of my previous comment, illustrates the point. Ms. Mueller hereby gives away the store.

"Keeping and using a long-barreled rifle for deer hunting or target practice is legitimate. I have hunted in Wisconsin. And I grew up with my family being avid big and small game hunters. My father loved hunting pheasants in southern Wisconsin with his faithful bird dog flushing out the birds."

Of course it is legitimate, but the Second Amendment nowhere mentions the right to keep and bear arms in connection with recreational shooting or hunting, and once again, it is not for Virtue, Mueller, any other hoplophobe or some state or federal legislature to tell us gun owners what kinds of firearms are "legitimate" for us and which are not.

"My father was an NRA member, but he never owned an AK-47 or an AR-15. He owned a 30.06, a 30-30 and an M-1. I learned to shoot using daddy's M-1."

Indeed. So? Many if not most NRA members today do own the AK, AR and other platforms. Her father's choice is irrelevant to us.

"Also keeping a pistol handy for protection against home invasion is within reason. A man's home is his castle. And at times that castle and castle dwellers (the family) have to be defended with deadly force. A baseball bat just doesn't cut the mustard or crack a head."

Ms. Mueller shoud then follow the logic: what if it's not just a lone crackhead but a band of heavily-armed maruaders? In that case one will want more than just a handgun. Something like, say, an AR or an AK with a goodly number of "high-capacity" magazines.

"The Second Amendment reads: "A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed."

Parsing the words "militia" basically means an armed civilian force backing up the rag-tag military in a time of extraordinary need.

We now have a well-trained military to provide the necessary security needed for a free state. Civilians rarely take up arms to defend the government."

Ms. Mueller could not have missed the point of the Second Amendment here more spectacularly. The reason the Antifederalists insisted on appending a Bill of Rights to the propsed Constitution is because they feared it would potentially lead to federal usurpation against the people and the states. (Turns out they were right.) The right of the people to keep and bear arms as enshrined in the Second Amendment was connected principally with, *but not limited to*, the right of a state to take up arms against the federal government and its armed forces that had turned tyrannical, and this is why her statement that "we now have a well-trained military to provide the necessary security needed for a free state" is absolutely absurd. Yes, "civilians rarely take up arms to defend the government", but it doesn't logically follow from this that nowadays civilians can just rest on their laurels and expect the government to be the good guys. Events happening today in Mordor-On-The-Potomac are illustrative of why that just isn't so.

"Nowadays the National Guard acts as the "well-regulated militia," since it is basically made up of civilians doing their civic duty during the time of civil crisis. Even my father was a Civil Air Patrol pilot. He liked to fly small single engine airplanes and had his civilian pilot's license."

Uh, no. Here is the current definition from the U.S. Code:

10 U.S. Code § 246 - Militia: composition and classes

(a) The militia of the United States consists of all able-bodied males at least 17 years of age and, except as provided in section 313 of title 32, under 45 years of age who are, or who have made a declaration of intention to become, citizens of the United States and of female citizens of the United States who are members of the National Guard.

(b) The classes of the militia are—

(1) the organized militia, which consists of the National Guard and the Naval Militia; and

(2) the unorganized militia, which consists of the members of the militia who are not members of the National Guard or the Naval Militia.

Subsection (b)(2) stems from the clear affirmations of the Founding Fathers that the "popular" or "constitutional" militia is not a state or federal miltary force, but *the people* themselves. Hence the wording of the Second Amendment's juxtapostion of "the people's" right to keep and bear arms and the preservation of a "well-regulated (meaning trained to arms) militia."

“A militia, when properly formed, are in fact the people themselves... and include all men capable of bearing arms.” Richard Henry Lee, The Letters Of Richard Henry Lee 1762-1778 V1

“Who are the militia? Are they not ourselves? Is it feared, then, that we shall turn our arms each man against his own bosom. Congress have no power to disarm the militia. Their swords, and every other terrible implement of the soldier, are the birthright of an American… The unlimited power of the sword is not in the hands of either the federal or state governments, but, where I trust in God it will ever remain, in the hands of the people.” – Tenche Coxe, The Pennsylvania Gazette, Feb. 20, 1788.

"As civil rulers, not having their duty to the people duly before them, may attempt to tyrannize, and as the military forces which must be occasionally raised to defend our country, might pervert their power to the injury of their fellow citizens, the people are confirmed by the article in their right to keep and bear their private arms.” in “Remarks on the First Part of the Amendments to the Federal Constitution,” under the pseudonym “A Pennsylvanian” in the Philadelphia Federal Gazette, June 18, 1789.

“I ask you sir, who are the militia? They consist now of the whole people.” - George Mason (Elliott, Debates, 425-426)

These are only a few of the quotations that can be adduced from the Founders demonstrating that they viewed the "well-regulated militia" to be the general populace, and that understanding is reflected in US Code 10 sec. 246 subsection (b)(2), as noted above. Anti-gunners like David Virtue typically scoff at this notion. Well, let them scoff, because it's true. It was true yesterday and it is true today, and Ms. Mueller is just flat wrong.

The next part of Mueller's goes on a bit of a tangent (poetry and such), until the end, where she gets it wrong again:

"The Second Amendment ensures the right of the citizens to keep and bear arms.

However, the Founding Fathers were dealing with muskets and flintlock pistols. They never envisioned the type of weaponry that are used, and more importantly, abused today."

And as I countered here:

"Gun-control advocates such as Virtue repeatedly trot out the trot out the tired, old argument that the Founding Fathers could not have foreseen the technological development of more potentially legal weaponry, but this false on its face. The Founders were learned men of the Enlightenment conversant with old and evolving technologies of all kinds, and they accordingly knew that military small arms technology would continue to evolve. Thomas Jefferson owned two Giradoni rifles, a precursor to automatic-fire technology. The Puckle Gun, patented in 1718, was an early Gatling Gun.

And with every new development of military small arms - muzzle-loading to breech loading, single shot to multiple shot (revolvers, lever action rifles and bolt-action rifles), to semiautomatics (late 19th century), to full automatics - American civilians were deemed to have just as much a right to access the evolving technology as the military did. This argument commonly spewed by hoplophobes that the Second Amendment does not guarantee the right to own "weapons of war" is thereby roundly refuted."

"During Colonial times, guns were vital to a household. They were used to provide meat for the family. A deer for venison, wild turkey and rabbit for the dinner table. Guns also provided protection against invaders -- be they two legged or four legged -- for the well-being and safety of the family."

While true, Ms. Mueller again ignores the Second Amendment's connection of the "right of the people to keep and bear arms" and the preservation of a "well-regulated militia". It makes no connection whatsoever between that right and the ability to kill game to feed one's family. It doesn't even link the right to self-defense, though the *constitutional history* behind the amendment does. The right to keep and bear arms in connection with self-defense was accordingly affirmed in Heller.

"I would imagine if the Second Amendment were to be penned today it would be written differently, taking into account the type of firearms we now have and the political climate."

Given the general intellectually diminished nature of today's American political class, that's surely true. Thankfully the Founders were much more learned and intelligent men and were able to enshrine the right in the Constitution when they did. The right of *individuals* to keep and bear arms is now settled law, so there's not much point in speculating what the American political class would do today.

"I do not see common sense gun control laws as an infringement against the Second Amendment. The people would still have "the right to keep and bear arms" but with practical limitations and community safeguards in place.

It makes no common sense that an 18-year-old cannot belly-up-to-the-bar for a beer, but waltz to a gun store for an AR-15."

Well again, says Ms. Mueller. Not only do we disagree with her notion of what "common sense" requires here, but we simply care nothing about her unlearned opinion on the matter. For us, it is perfectly reasonable for a qualified 18-year old to purchase an AR-15, especially since he's old enough to enlist or be drafted and fight in a war bearing *true* assault weapons.

The rest of Ms. Mueller's article is merely a meandering ramble, where I believe she gets a few things right, though they're not about gun control per se but instead the terrible spiritual and cultural problems that plague modern society and which is the *major contibutor* to gun-related violence. It may be worth your while, so read on in Virtue Online article if you choose. I've addressed all I need to address in this reply.

David Virtue's Irrational Hoplophobia - Part 4 in a Series

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Wednesday, August 10, 2022 at 05:40PM

Wednesday, August 10, 2022 at 05:40PM The following is a postscript to David Virtue's 2-17-18 commentary entitled "Gun Madness in America: Avoiding The Obvious", to which I responded in a post below. Again, my responses here will be in italicized bold:

"Dear Brothers and Sisters,

www.virtueonline.org

February 23, 2018

In a God-n-Guns culture, evangelicals can usually be counted on to side with guns as part of the call to freedom and "rights" found in the Second Amendment. However, after the recent Florida school shooting which left 17 dead, evangelical leaders have called for action amid what they called a "moral emergency".

A petition calling for 'action' as well as prayer was signed by pastors, church leaders and others with influence who urged the faith community to acknowledge their biblical responsibility to protect life amid the nation's gun violence epidemic.

"As we mourn for our brothers and sisters who have died, we pray fervently for their friends and family who grieve. We also accept and declare that it is time to couple our thoughts and prayers with action," the petition states. "We call on our fellow Christian believers, church leaders, and pastors across the country to declare that we will decisively respond to this problem with both prayer and action."

The petition has already been signed by a number of leaders, including Rev Dr. Rob Schenck, president of The Dietrich Bonhoeffer Institute and the subject of the Emmy award-winning gun violence documentary The Armor of Light; Dr. Joel C Hunter, faith community organizer and retired senior pastor of Northland Church; Lynne Hybels, co-founder of Willow Creek Community Church; Dr. Preston Sprinkle, teacher, speaker and New York Times best-selling author; and Kathryn Freeman, director of public policy, Christian Life Commission, Texas Baptists (The Baptist General Convention).

Schenck said; "If the solution to this deadly disease in American society is more guns, then the United States -- with over 300 million weapons in general circulation -- would be the safest place on earth. We have a moral emergency in our country. It's time we wake up, face it, and fix it. Now. Fellow faith leaders, I hope you'll join myself, along with other church leaders and pastors and sign this petition letting the rest of our nation know that we're committed to responding to the gun violence plaguing our nation with both prayer AND action."

The deeper question is; "If not now, when? When will Christian leaders and all people of faith, the moral leaders of our society, recognize that our culture has so radically changed from the one that established the Second Amendment that its intent would now be better fulfilled with common sense qualifiers.

"In a society that is normalizing violence daily by constant news focus, video games and epidemic anger, why not at least keep weapons of mass murder out of the hands of the insane and the untrained? Such a movement will not start with politicians who are simply angling toward their own reelection. It is up to us."

Yes, Evangelicals *can* usually be counted on to side with gun rights, and that's why what Mr. Virtue references in this postscript is representative of a minority position. Schenk, for example, has long been known to be a hoplophobe, which is precisely why the vast majority of American Evangelicals ignore him.

Evangelical anti-gunners such as Schenk and Virtue clutch their pearls at the thought of "over 300 million weapons in general circulation", but what do they propose to do about it? Circulate a petition? Please. The purpose of petitions is to hopefully influence the Powers That Be to "do something" about gun-related violence. Do Something. Anything. Anything at all. That is the measure of the folly of gun-control activists. Just please, Congress, pass any law you can, no matter how ill-reasoned, and they have managed to pass a few.

However, what have any of the laws they've managed to get on the books done so far to address the problem of gun-related violence? Nothing, that's what. There are still hundreds of millions of guns and "high-capacity" magazines in American hands, and counting. There are probably a billion or so rounds of stockpiled ammunition, and counting. Combine this with the unpleasant reality that we live in an increasingly nihilistic culture, and the conclusion follows that gun-related violence only promises to get worse.

And this is why, as American sociologist Amitai Etzioni argued in a Communitarian Network journal article entitled "The Case for Domestic Disarmament" (apparently no longer accessible online), "vanilla-pale" measures such as background check requirements will never solve the problem of gun-related violence. The only way to solve it, Etzioni argues, is to effectively disarm Americans through banning the sale and possession of firearms coupled with a national gun buyback program. Etzioni reasserted that argument in a 2013 Huffington Post article. This is more or less what happened in Australia in 1996 and 2003 when the Australian government banned most weapons and attempted to collect them through buyback programs in the wake of horrific gun-related crimes. Mr. Virtue routinely touts the Australian "solution" as one that should be followed in the United States.

However, as David Kopel and I countered Etzioni in a Maryland Law Journal article, "Communitarians, Neorepublicans and Guns: Assessing the Case for Firearms Prohibition", all this is just a laughable pipe dream, not to mention wholly unconstitutional. It's simply not going to happen here in the United States, especially now that the United States Supreme Court has opined clearly on the matter. Even if by some stretch of the imagination a future United States enacted such laws, it would be almost universally disobeyed, and worse, would likely touch off an American civil war.

A civil war with hundreds of millions of Americans fighting it against vastly outnumbered national law enforcement officers and military personnel (many if not most of whom would join the resistance, as they are even now). (See Second Amendment Sanctuary Movement.)

Christian anti-gun activists such as Virtue and Schenk are therefore engaged in nothing more than a monumental exercise of wishful thinking. Guns are here to stay here in America. Hundreds of millions of them, including handguns and scary looking military-style semiautomatics. The resolve of the American gun culture to keep it this way is expressed here. "We will not disarm": "Memorandum on Arms and Freedom"

David Virtue's Irrational Hoplophobia - Part 3 in a Series

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Wednesday, August 10, 2022 at 05:39PM

Wednesday, August 10, 2022 at 05:39PM Gun Madness in America: Avoiding the Obvious, an article Mr. Virtue posted in Virtue Online on February 17, 2018. In this reply and subsequent ones I will respond to salient passages in italicized bold. The reader will need to refer to the article for context:

"Another round of gun madness, another round of killings, the 18th school shooting so far this year. More can be anticipated. Since 2013, there have been nearly 300 school shootings in America — an average of about one a week with no end in sight because of the collective amnesia by Washington politicians, the NRA and millions of Americans who believe that freedom can only be found spurting bullets from the end of a gun."

"The NRA and millions of Americans who believe that freedom can only be found spurting bullets from the end of a gun." That, ladies and gentlemen, is kind of misrepresentative, hyperbolic and emotive rhetoric to which Virtue repeatedly resorts in his anti-gun arguments. As you will see in this post and in the next few parts to this series, it is all he can muster (no pun intended.)

"America needs to ban assault weapons like the AR-15 because they serve no purpose but to kill another human being. No one is safe in America any more. You can be in a school, church, supermarket, shopping mall or theatre. You can be in a rich or poor neighborhood, a so-called “gun-free zone” and still you risk your life."

Mr. Virtue is either oblivious to or willfully suppresses the fact that *all* weapons are designed to kill human beings, or animals or both. That is what a "weapon" is. Moreover, not for Virtue, apparently, is the fact that the right to keep and bear arms as enshrined in the Second Amendment to the United States and as reaffirmed by the United States Supreme Court in the Heller, McDonald and recent Buren decisions protects exactly the kind of firearms he decries, mainly firearms suited for military use (e.g., the AR platform). The Second Amendment, which at the time of its drafting had neither recreational shooting or hunting in mind, but in connection with the needs of a "well-regulated militia". This was affirmed in the 1939 US Supreme Court decision U.S. v. Miller.

At the time of the amendment's drafting and adoption, black powder rifles, handguns and other small arms were the weapons used by the militia and Continental Army. And the amendment says the "the people" have the right to own such arms. Gun-control advocates such as Virtue repeatedly trot out the tired, old argument that the Founding Fathers could not have foreseen the technological development of more potentially lethal weaponry, but this false on its face. The Founders were learned men of the Enlightenment, conversant with old and evolving technologies of all kinds, and they accordingly knew that military small arms technology would continue to evolve. Thomas Jefferson owned two Giradoni rifles, a precursor to automatic-fire technology. The Puckle Gun, patented in 1718, was an early Gatling Gun.

And with every new development of military small arms - muzzle-loading to breech loading, single shot to multiple shot (revolvers, lever action rifles and bolt-action rifles), to semiautomatics (late 19th century), to full automatics - American civilians were deemed to have just as much a right to access the evolving technology as the military did. This argument commonly spewed by hoplophobes that the Second Amendment does not guarantee the right to own "weapons of war" is thereby roundly refuted.

"On Wednesday, Nikolas Cruz killed 17 people at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. He was able to purchase a deadly assault rifle quite legally, yet was legally prohibited from buying a hand gun. The tragedy has left grieving families broken and a community shattered. It also showed up America as being the only country in the world that allows its citizens unfettered access to semi-automatic weapons."

Well, Mr. Virtue will have to take that up with America's Founding Fathers, whose political philosophy was quite different than that of the Kiwis, Aussies, Brits and Europeans on this and other matters, as well as with the United States Supreme Court.

An evangelical movement calling itself Prayers and Action for Gun Safety had this to say:

“To the rest of the world, the situation looks insane. No other nation on earth would put up with this level of violence if it could stop it. America accepts it as a price worth paying for the right to bear arms. Fanatical gun-rights campaigners resist any infringement on those rights. . . .

Resisting gun control on principle is faithlessness, they say. “Christians ought to be the first to call for serious talks about how to reduce the number of gun deaths in America. And if that means giving up some costly 'freedoms', evangelicals ought to be first in line. Because when freedom becomes an excuse for doing wrong, or allowing wrong, it's corrupted (Galatians 5:13).”

Perhaps Mr. Virtue should explain precisely why left-leaning Evangelical organizations unstudied on this issue are any more competent to pontificate on it than he is. In another article he has essentially admitted that this is a minority position among American Evangelicals.

"In 1996, Australia introduced major gun law reforms that included a ban on semiautomatic rifles and pump-action shotguns and rifles and also initiated a program for buyback of firearms. From 1979-1996 (before gun law reforms), 13 fatal mass shootings occurred in Australia, whereas from 1997 through May 2016 (after gun law reforms), no fatal mass shootings occurred."

Indeed. So? As noted above, the United States is not Australia, and if recent events in that country and other Commonwealth countries are any indication, it's a good thing. No wonder such regimes want draconian gun laws. Mr. Virtue needs to listen carefully: *we do not follow Australia's or New Zealand's lead* on this and any number of other political issues, such as the right to free speech. (Ahem.)

"And the same arguments over the same issues are rehearsed in the same words by the same people. Among them is the plea not to use this event to push for gun control, because now is a time for grieving, not for politics. Nonsense. After Sandy Hook wherein 28 people died, the NRA moved in and exhorted parents of kids still alive to buy even more guns to fight against an imaginary enemy in the name of “freedom”. The Russians never came, ISIS is on the ropes, Al Qaeda and the Taliban will never darken American homes. And the government will never come to take away over 300 million guns already out there."

Virtue is right about one thing: the government *will* never come to take away over 300 million guns already out there. Even if gun confiscation became law in flagrant violation of both state and federal constitutions, the United States government does not have the wherewithal to do it, and what's more, most American law enforcement and military do not have the will to do it. It would mean suicide for many of them, not to mention civil war. But again the paragraph above is nothing more than a highly rhetorical bird's nest of confusion. There is nothing logically compelling about it at all.

"From a national-security standpoint, the Amendment’s suggestion that a “well-regulated militia” is “necessary to the security of a free State,” is quaint. The Minutemen that will deter Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong-un are based in missile silos in Minot, N.D., not farmhouses in Lexington, Mass."

A statement which indicates that Mr. Virtue needs to spend some quality time in a library researching 4th-Generation Warfare. In his watershed Yale Law Journal article "The Embarrassing Second Amendment", liberal law professor Sanford Levinson, who stated at time that he was neither a gun owner nor a gun-rights activist, wrote this: "It is simply silly to respond that small arms are irrelevant against nuclear-armed states: Witness contemporary Northern Ireland and the territories occupied by Israel, where the sophisticated weaponry of Great Britain and Israel have proved almost totally beside the point. The fact that these may not be pleasant examples does not affect the principal point, that a state facing a totally disarmed population is in a far better position, for good or for ill, to suppress popular demonstrations and uprisings than one that must calculate the possibilities of its soldiers and officials being injured or killed."

Determined insurgencies are rarely defeated by powerful states. Levinson and Michael S. Lind, who has written extensively on 4th-Generation Warfare, explain why if Virtue is up for some study.

"From a personal liberty standpoint, the idea that an armed citizenry is the ultimate check on the ambitions and encroachments of government power is curious. The Whiskey Rebellion of the 1790’s, the New York draft riots of 1863, the coal miners’ rebellion of 1921, the Brink’s robbery of 1981 — does any serious conservative think of these as great moments in Second Amendment activism?"

The mind boggles here. The Whiskey Rebellion, the New York draft riots, the 1921 coal miners’ rebellion of 1921, and the Brink’s robbery of 1981 are arguably great moments in Second Amendment activism? Please, David.

"An editorial in The New York Times called for a repeal of the Second Amendment. “I have never understood the conservative fetish for the Second Amendment. From a law-and-order standpoint, more guns means more murder. States with higher rates of gun ownership had disproportionately large numbers of deaths from firearm-related homicides,” noted one exhaustive 2013 study in the American Journal of Public Health.”

It won’t happen of course. “A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” Former Chief Justice Warren Burger Justice called it a “fraud on the American public.” That’s how he described the idea that the Second Amendment gives an unfettered individual right to a gun. When he spoke these words to PBS in 1990, the rock-ribbed conservative appointed by Richard Nixon was expressing the longtime consensus of historians and judges across the political spectrum."

Yes, well, Burger was speaking in his capacity as a private individual expressing a personal opinion after he left the US Supreme Court. And the US Supreme Court has since then roundly refuted Burger's opinion. It has no legal relevance whatsoever. Why? Because he was factually wrong.

As an aside, Burger was not, as Virtue asserts, a "rock-ribbed conservative": "Although Burger was nominated by a conservative president,[1] the Burger Court also delivered some of the most liberal decisions regarding abortion, capital punishment, religious establishment, and school desegregation[2] during his tenure.[3]" (Wikipedia)

"But sometimes, that's just the point at which politics becomes personal enough for something to change."

Mr. Virtue needs to elaborate on how he proposes to change settled constitutional law. He and his fellow hoplophobes need to understand that they've lost this war and are going to have to find a better narrative.

" So the violence continues and nothing will happen because there isn't the political or social will to change anything. And cynical politicians, too afraid of upsetting the NRA and it cohorts and millions of brainless gun owners who believe freedom comes with collateral damage if you should just happen to get in the way of a bullet, will continue."

See, as I noted previously, this is standard emotive David Virtue fare. "The NRA and its cohorts and millions of brainless gun owners." Consider such inflammatory rhetoric and what it reveals about the way Virtue "thinks" with respect to this issue. In this post below, Virtue calls his interlocutor, who happens to be a Facebook friend of mine, "you idiot" and flames on about "AHOLE America." This isn't the mark of a sober Christian thinker but of a man driven by anger, and as I told Mr. Virtue in that post, St. John Cassian once said something to the effect that anger dulls the intellect. And that is precisely the dynamic operating in all of Virtue's tirades against our constitutional right to keep and bear arms.

David Virtue's Irrational Hoplophobia - Part 2 in a Series

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Wednesday, August 10, 2022 at 05:28PM

Wednesday, August 10, 2022 at 05:28PM n. Irrational, morbid fear of guns (coined by Col. Jeff Cooper, from the Greek "hoplites," weapon). May cause sweating, faintness, discomfort, rapid pulse, nausea, sleeplessness, more, at mere thought of guns. Hoplophobes are common and should never be involved in setting gun policies. Point out hoplophobic behavior when noticed, it is dangerous, sufferers deserve pity, and should seek treatment. When confronted, hoplophobes typically go into denial, a common characteristic of the affliction. Often helped by training, or by coaching at a range, a process known to psychiatry as "desensitization," often useful in treating many phobias.

Also: Hoplophobe, hoplophobic. -

The person had hoplophobia and passed out at the mere sight of a gun." - Urban Dictionary

This definition from the Urban Dictionary, while clearly somewhat ideological and hyperbolic, nevertheless hits the mark, and it especially hits the mark with respect to the rants of "Dr." David Virtue (his doctorate is an honorary doctorate, not an earned one), a recent Baptist and now Anglican who hails from the People's Republic of New Zealand.

Read here for a summary of a recent report of mine with respect to his latest rants.

I have good reason to believe that David has seen that blog post below and my comment challenging him to reply here publicly. He's apparently not having any.

David Virtue's Irrational Hoplophobia - Part 1 in a Series

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Sunday, August 7, 2022 at 11:18PM

Sunday, August 7, 2022 at 11:18PM Edit: I have some reason to believe that Mr. Virtue has seen this challenge. If I am right, let us see if he can manage to rise to the occasion. The comments are open for you, David.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Most of you in our shared Anglican circles know David Virtue and his news congregator/blog Virtue Online, "The Voice For Global Orthodox Anglicanism."

David is an expatriate Kiwi, who actually believes that New Zealand provides some sort of model for rational government that the United States should emulate, is left-leaning and therfore actually irrational on this issue and no doubt others, as so many in the Commonwealth are. They mindlessly defer to their goverment and the elites who run them. They have no understanding of our contitutional government and how it has preserved the historical rights of Englishmen, whereas the UK and the Commonwealth, rejecting that legacy, have failed to do so.

This became clear to me a number of years ago when I debated him off and on about the right to keep and bear arms as guaranteed by the Second Amendment of the United States Constitution. He ended up blocking me on Facebook and apparently has made it impossible for to me post comments on Virtue Online articles. Oh well.

The following is a representative example from a friend's Facebook page of his latest "thoughts" about this issue.

Virtue: "Until we bring gun madness under control it is all going to get worse, nothing can stop the uncontrolled killing, nothing. America is doomed,only and unless America follows NZ and Australia and bans semi automatic weapons."

Interlocutor: "Yes and be under the authoritative thumb of govt as AU and NZ are today. We're good. Drugging kids up is bringing society down. Marriages, divorce, God are much larger components. Totalitarianism is horrific."

Virtue: "New Zealand and Australia are democracies you idiot. They have free and fair elections, they don’t elect malignant narcissists like trump…and they don’t allow guns as European countries don’t either and their life expectancy is eight years better than America."

Interlocutor: "Idiot? You are joking right? You can't own a gun to protect against anyone including over reaching govt. You're DICTATED to get shots which haven't been vetted. They are closing in on homeschoolers. They have their own thought police and "disinformation bureau. Add in England as well which is also seeing an uptick in guns and deaths by knives. Please David. . . . not elected narcissists? NZ minister shuts down entire country. Australian govt arrests parents who aren't COVID shot? Narcissists?"

Virtue: "The odds of someone appearing at your front door with a loaded gun is .0000000002 percent, and if they did you would not know and could not protest yourself anyway. No civilized country allows its citizens to own a AR15s and 9 millimeter glocks. NZ and AUSTRALIA allow hunters (and the police) to have guns and they have to lock them away till needed, Only AHOLE America allows any citizen with $100 bucks to buy a gun and let's see if we can raise the death from 40,000 to 100,000 a year along with the one million idiots who would not take the vaccine."

Virtue: "America has a pop.of 330 million, there are 400 million guns. America is awash in guns…the killings will continue. America as a democracy is done for.

It's hard to know where to begin with all this. Mr. Virtue says we are doomed unless we adopt the draconian gun control legislation of Australia and New Zealand. He avers that AU and NZ are "democracies", and anyone who demurs or who sees the devil in the details is an "idiot", and then launches into a rant fueled by his obvious Trump Derangment Syndrome. Then he cites the low risk of some criminal appearing at our front door, leaving us wondering if he has any insurance policies. Then he says, "No civilized country allows its citizens to own a AR15s and 9 millimeter glocks", begging the fundamental constitutional question as far as the United States is concerned. Then, in exemplary Christian fashion, he refers to "AHOLE America" (stay classy, David) and sets forth some fantasy about arms being available for $100.

And then goes off about the vaccination controversy. What!?

Mr. Virtue's rant is a veritable bird's nest of mental confusion and mistatement of the facts wrapped up in an exercise of pure, unfocused rant.

St. John Cassian said (paraphrased), "Anger dulls the intellect", and it surely does in Virtue's case.

We are not the UK, Canada, Australia or New Zealand, David. We are the United States of America, and in the United States of America we have the right to keep and bear arms, including scary black ones, and we're not about to listen to Kiwi hoplophobes like you.

Part 2

Non Sequitur

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Wednesday, August 3, 2022 at 12:07PM

Wednesday, August 3, 2022 at 12:07PM "When Jesus told the Roman governor Pontus Pilate that his kingdom was not *of* this world, he closed the door on any possibility of a worldly Christian nation or empire.

There is the peaceable kingdom of Christ and there are the warring nations of this world, and there can be no conflation of the two.” - Brian Zahnd

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is pure rubbish. It simply does not follow either logically or exegetically (and hence a non sequitur) that because Christ's kingdom is "not of this world" the door is closed to the possibility of a Christian nation. We currently live in a dialectical eschatological tension between the "already" and "not yet", and in accordance with this the possibility of a Christian nation cannot be foreclosed. One does not need to be a postmillennialist to hold this position. More importantly, when we consider all the alternatives, a Christian nation emerges as the best of all possible states.

"What *do* they teach them at these schools"?

Another Shameless Plug for the Orthodox Anglican Church

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Tuesday, July 5, 2022 at 05:47PM

Tuesday, July 5, 2022 at 05:47PM I have the honor of being ordained a priest in the OAC on the same day that Fr. Smith was incardinated into the OAC at Resurrection Anglican Church, Kannoplis, NC, June 22, 2018.

Fr. Smith is an exemplary priest and historical and political thinker.

I'll Just Leave This Here

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Saturday, July 2, 2022 at 01:03AM

Saturday, July 2, 2022 at 01:03AM From a neo-Anglican priest I know:

So, the Supreme Court has paved the way for states to be anti-abortion by policy. Sadly many who are praising the decision of those wielding unelected power the loudest, aren't actually concerned with truly being pro-life... only anti-abortion.

#GunReform #PrisonReform #AbolishDeathPenalty #NeedlessWars #Homelessness #Racism

Words fail.

Two New Bishops Elect of the Orthodox Anglican Church

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Sunday, June 5, 2022 at 04:18PM

Sunday, June 5, 2022 at 04:18PM I can't speak too highly of these men, both of whom I know.

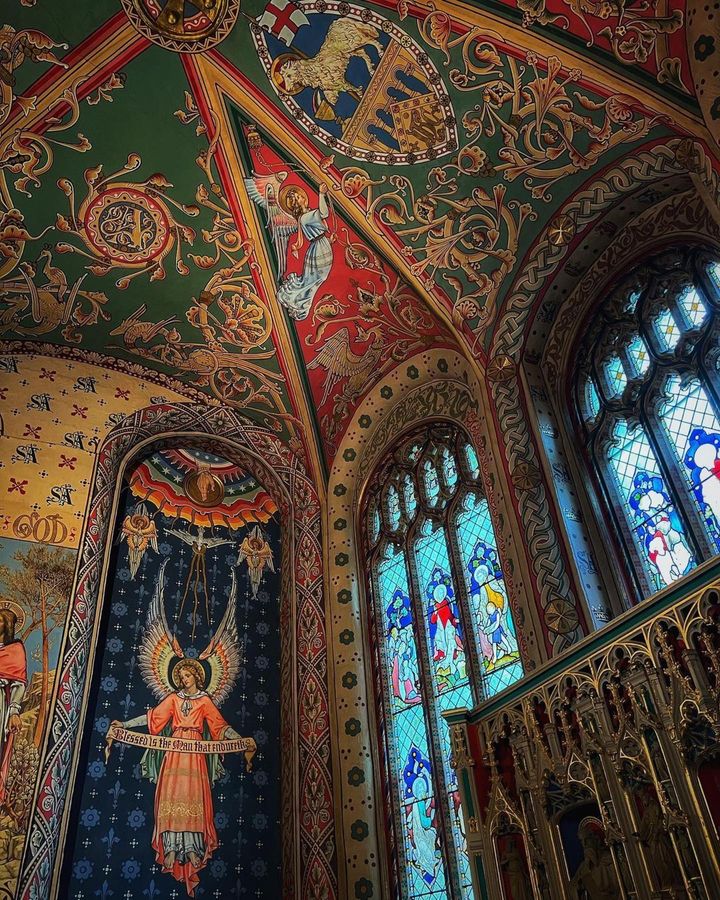

Why Our Churches Should Be Beautiful

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Tuesday, May 31, 2022 at 11:12PM

Tuesday, May 31, 2022 at 11:12PM Rabekah Henderson at Mere Orthodoxy.

"A beautiful church is not something that is only reserved for centuries-old mainline denominations, or congregations with resources to spare. Instead, a beautiful church can be a powerful witness to the community, connect us with the traditions of our ancient and sufficient faith, remind us of the beauty of God and his provision, and shape our spiritual formation week-in and week-out. Beauty in the church should not be an afterthought, but instead a key consideration as we design the spaces we worship our magnificent and glorious God in."

On The AR-15

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Monday, May 30, 2022 at 08:10PM

Monday, May 30, 2022 at 08:10PM All liberals and some conservatives (religious and political) will write me off when I say that American gun control activism is of the Evil One. I don't give a tinker's damn about their opinions. I really do believe that my former and present gun-rights activism constitutes a war against the devil. That's my story and I am sticking to it. Hear me out.

First, for the devil to achieve his goals against traditional Christian culture, he is going to have to wage an intense war against those parts of the former Christendom that harbor gun cultures. He has been largely successful throughout the Commonwealth due to its benighted Hobbesian deference to government. The citizens of the UK, Canada, Austrialia, New Zealand et al. have essentially surrendered their arms to the state. And that having been done, just look at how that those states are now coming against the traditional rights of Englishmen and the Church. Our American Founding Fathers knew this, and they warned us against it, and they therefore set some things into fundamental American law, arguably the most important of which is the right to keep and bear arms.

Second, in John 8:44 Jesus said that Satan "was a murderer from the beginning." And so he takes GREAT delight in advancing his war against traditional Western culture, liberty and the Church by sending crazed gunmen to slaughter children. He gets two for the price of one.

I am convinced that I am accurately assessing this thing. Change my mind.

And that being what it is, I excoriate conservative Christians who are in a dalliance with liberal hoplophobes, including a few trad Anglicans I know. For some inscrutable reason they find themselves hauling water for religious leftists. I find it just absolutely astounding.

So I will just come out and say it right here with reference to C.S. Lewis' "The Last Battle": if you support banning weapons like the AR-15, you serve Tash (though you might get let off the hook if you're Puzzle).

ACNA,

ACNA,  Anglican Follies,

Anglican Follies,  Anglican Realignment,

Anglican Realignment,  Bernard Option,

Bernard Option,  Bernard of Clairvaux,

Bernard of Clairvaux,  C.S. Lewis,

C.S. Lewis,  Christian Culture,

Christian Culture,  Christian Pacifism,

Christian Pacifism,  Christian Resistance Theory and Praxis,

Christian Resistance Theory and Praxis,  Historical Theology,

Historical Theology,  Holy Scripture,

Holy Scripture,  Just War Doctrine,

Just War Doctrine,  Liberal-leftism,

Liberal-leftism,  Man-glicanism,

Man-glicanism,  Muscular Christianity,

Muscular Christianity,  Neo-Anglicanism,

Neo-Anglicanism,  Political Theory and Praxis,

Political Theory and Praxis,  Right to Keep and Bear Arms

Right to Keep and Bear Arms Dreher: Babylon's Furnace

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Thursday, May 12, 2022 at 09:40PM

Thursday, May 12, 2022 at 09:40PM The latest and greatest from Rod Dreher at Touchstone Magazine.

Dreher is one of my favorite religio-political writers (Eastern Orthodox), though I find myself at odds with him now and again. But here he sets forth, once more, an argument for the need of the Church to start moving en masse into a "Benedict Option" mode for those of us in the "liberal democratic" West. I would add a measure or two wrt to his defense of Christian resistance, which I have posted here under a category I have named the "Bernard Option.”More Trouble in the ACNA

Embryo Parson Posted on

Embryo Parson Posted on  Thursday, May 12, 2022 at 09:22PM

Thursday, May 12, 2022 at 09:22PM The ACNA boasts of its growth, but one must ask whether its vaunted "growth" has become too big for the managing; whether quantity is eclipsing quality.

Could an ANCA diocese go bankrupt? Joel Wilhem blogging at A Living Text. Tales of a Roman-Catholic like coverup.

The controversy revolves in part around Bishop Stewart Ruch. Here is Ruch & Co. at "Rez" "Anglican" church on the day of his consecration as bishop: